More People: South Bend Survived

This is the introduction to an article and podcast series by Joe Molnar titled More People: How South Bend Lost 50,000 People in 50 Years. Joe is a proud 4th generation son of South Bend.

Read the original series: Introduction | One | Two | Three | Four | Five | Six | Seven

Read the census recap: Introduction | One | Two

Subscribe to the podcast: Apple | Spotify | Google | Stitcher | TuneIn

Riverside Drive in 1914 from a postcard printed by Miller's Book Store in South Bend.

We have come to the end of the More People story. This series has specifically been the story of my city, South Bend, Indiana. The tale of her collapse from a mid-century population height to a post-Great Recession bottom. I have done my best to tell the story truthfully, relying on the facts to guide me to their inevitable conclusions.

However, there is a side of the story that has largely been missed so far. We now know why people left, but why did thousands of others stay? What made South Bend attractive enough for people to weather the storm of decline or – even more puzzling – choose to make it their new home? Much focus has been paid to the thousands of residents who left South Bend over the past six decades, but there are far more people who have decided to stay. It is in their stories that we find hope for the future and an end to the series.

More People has explored the number of factors that lead to a population decline in South Bend. These included a number of local, regional, and national trends, including: deindustrialization, suburbanization, and white flight; national population trends toward the south and west and against the north and east; federal programs such as Urban Renewal incentivized cities to destroy their urban cores; a global housing crash which harmed marginal housing markets disproportionately; and government policies on every level explicitly or implicitly harming African Americans, such as the refusal to issue Veterans Affairs loans to returning Black World War II veterans. When taking them all together, South Bend’s collapse becomes remarkable not because the city lost so many people but because so many remained. While our series has focused on how and why South Bend lost nearly 30,000 residents since its peak population in 1960, we must also consider how the city managed to hold onto over 100,000 residents.

In order to understand the quality of the city’s response to its population crises and analyze how much worse – or better – it may have been, it is imperative to analyze the city against its peers. During the middle of the 20th century, the Midwest was dotted with dozens of small, midsize, and larger cities. While these cities shared many characteristics, it would be illogical to compare South Bend’s story with the likes of the megalopolises such as Chicago or state capitals like Columbus and Madison. For the purpose of our study, we need to analyze cities which looked like South Bend at its own peak population.

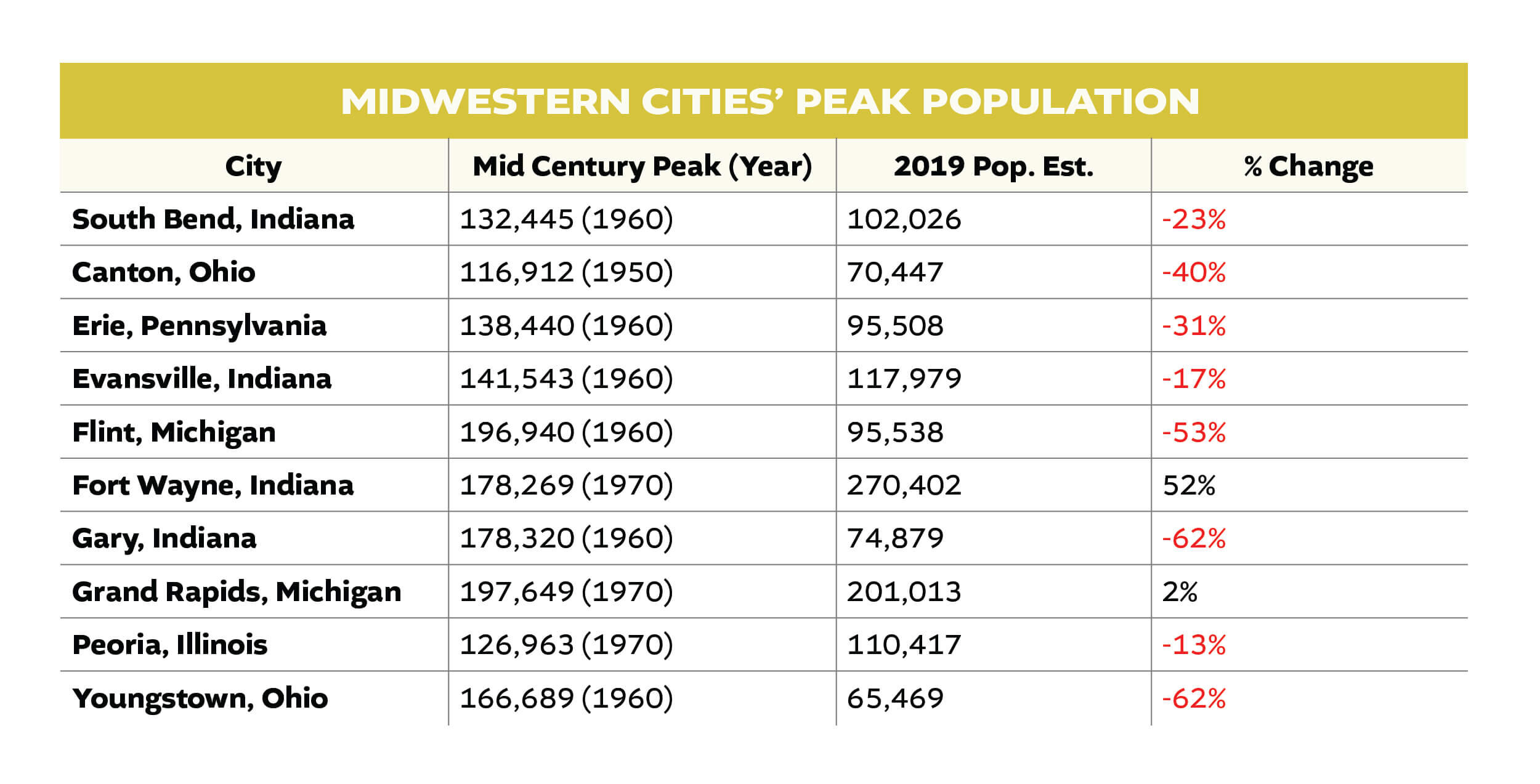

With that in mind, we will compare South Bend against nine other cities in the Midwest. These cities all had a mid-century population between 100,000 and 200,000, were heavily dependent on a manufacturing economy, and were the primary central city and population center for their respective counties. The nine cities are as follows: Gary, Indiana; Youngstown, Ohio; Peoria, Illinois; Flint, Michigan; Erie, Pennsylvania; Canton, Ohio; Evansville, Indiana; Grand Rapids Michigan; and Fort Wayne, Indiana.

All have unique geographies, peoples, and economic forces imposed upon them. However, analyzing this group helps see the different paths South Bend could have taken with the forces marching against it. Below is a chart detailing each city at its mid-century population peak (some cities peaked in 1970, while others in 1960, and Canton peaked in 1950) and the percentage decline or even gain since the 20th Century peak. It is important to note all 10 of the cities experienced at least one decade of population decline.

Looking at the breakdown of these 10 cities, we can place them into three rough camps of population change since the mid-20th century. First, the two cities that grew their population: Grand Rapids and Fort Wayne. Second, those that had a moderate drop of population between zero and 35%: South Bend, Erie, Evansville, and Peoria. And lastly, those cities which experienced a substantial collapse in their population, over 35%: Canton, Flint, Gary, and Youngstown. These three buckets show the different paths which were available to a mid-size manufacturing city.

South Bend can be placed solidly in the second grouping. In fact, South Bend weathered the pitfalls of the last six decades adequately well compared to her peers. In 1960, South Bend was the eighth largest of the 10 cities. Today, South Bend is the fifth largest of the group, and only one city that used to be smaller than South Bend, Peoria, is now larger. Furthermore, South Bend’s 23% loss of its peak population also places it as the fifth best of the cities identified. Two cities – Fort Wayne and Grand Rapids – gained population, and two other cities – Peoria and Evansville – suffered from a slightly smaller population decline than South Bend. The other five cities suffered significantly worse population decline.

Taken together, South Bend’s decline of 23% did slightly better than the average decline of 24.7% across the 10 cities and pointedly better than the median decline of 27%.

We have spent the last six articles exploring why South Bend lost a quarter of its peak population. There is little reason to rehash those details, but why did South Bend do slightly better than the average mid-size Rust Belt city?

Reason One: Overall County Growth

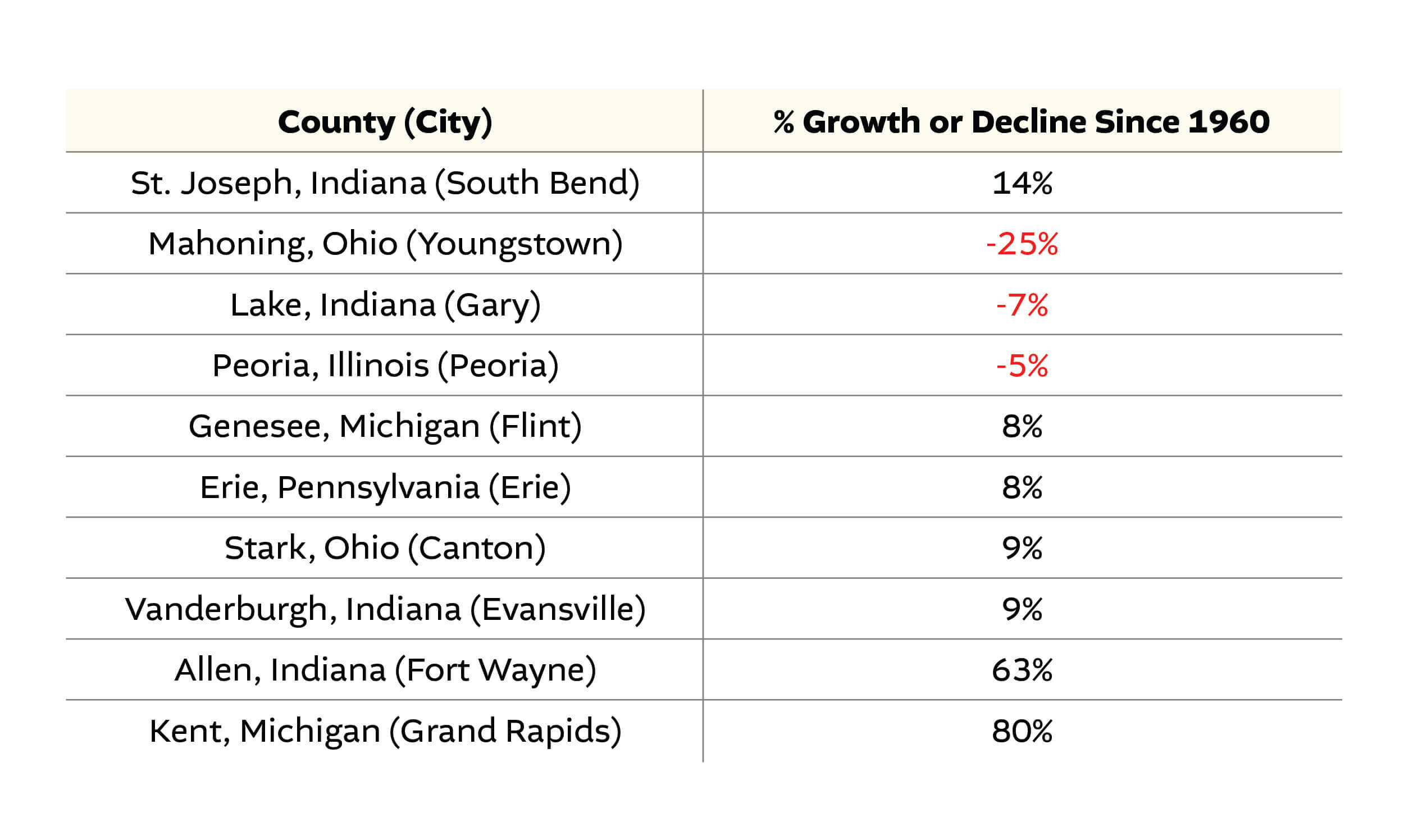

As More People has explored in previous articles, St. Joseph County’s overall population continued to rise despite South Bend’s population decline. Much of the county’s growth was due to South Bend residents moving outside of the city boundaries and fighting the city from annexing them. However, about half of St. Joseph County’s growth was due to an influx of people from outside of the county.

This population growth in the county and region overall helps identify the first reason as to why South Bend did not suffer a worse population decline. St. Joseph County had the third highest growth of all counties analyzed and the most growth of any counties which had a primary city lose population.

Some of South Bend’s success in avoiding the collapse other similar Rust Belt cities experienced is the relative growth of the South Bend region. However, county growth does not necessarily mitigate city decline. For example, Flint, Michigan has lost 53% of its peak population while its county grew by 8% during the same time period. The city of Peoria represents the other side of the coin; both the county and the city have lost moderate amounts of population.

Reason Two: Jobs Stayed in South Bend

As discussed in Part IV, “Jobs Stayed in South Bend, but Employees Left,” we discussed at length how South Bend did not experience a total collapse of employment, which is usually the assumption when discussing population decline. Rather, employers remained in South Bend and their employees left for the suburbs.

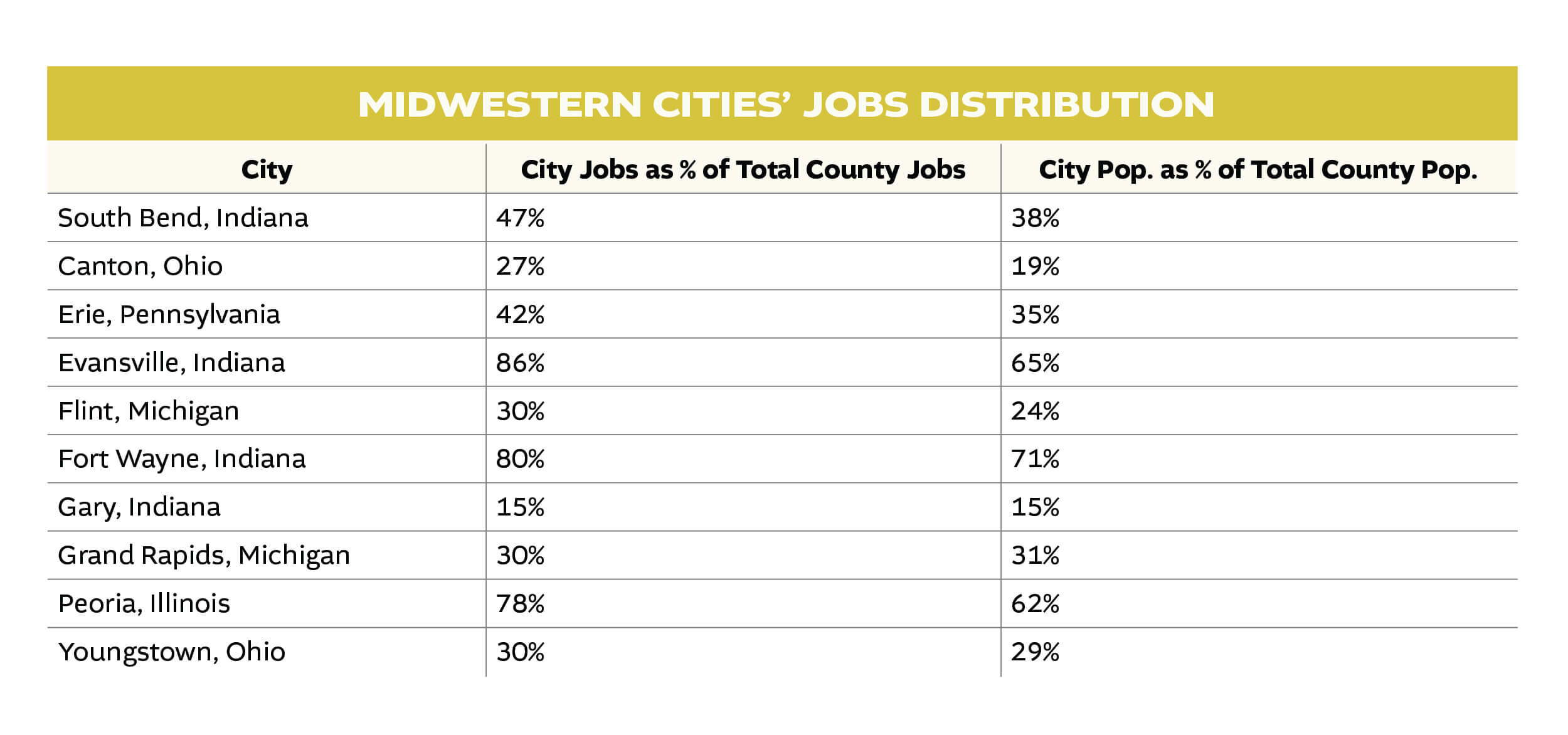

South Bend has a larger percentage of jobs in its county than population. And the inverse is true for the cities which struggled the most.

The chart above demonstrates that the South Bend’s phenomenon of having a larger percentage of jobs in the county than people in the county was replicated across the Rust Belt. Even cities such as Canton, Ohio – which suffered nearly twice the percentage decline in population as South Bend – has significantly more jobs than people in relation to the total county.

The three cities which experienced an over 50% drop in population since their peak – Flint, Youngstown, Gary – all have nearly the same ratio of jobs to people in their respective counties. Many of the most successful of the 10 cities in terms of retaining population also have retained their prominent positions as the job centers of their counties. While job growth and decline does not neatly equal population growth and decline, a city remaining the job center for the surrounding area helps stem dramatic population decline.

Reason Three: The emergence of higher education and medical sectors

One factor uniting all 10 cities is the decline in manufacturing. That is, of course, why these cities are part of what is considered the Rust Belt. All suffered a decline in manufacturing in the second half of the 20th Century. For most of that time, people living in Rust Belt cities hoped new industries would come and help cushion the blow of deindustrialization. To a certain respect, this happened in South Bend and helped mitigate population decline within the city.

Jason Segedy, an urban planner with the City of Akron and a Legacy Cities Fellow for the Economic Innovation Group, wrote regarding the Education and Medical fields for Rust Belt cities:

“The ‘Eds and Meds’ economy has sustained legacy cities across the country, to varying degrees, since the collapse of manufacturing that began in the 1970s. The healthcare and education economy has affected each of these cities differently, ranging from Pittsburgh, where it has been transformative; to Baltimore and Cleveland, where the results are a bit more mixed; to cities like Youngstown and Flint, where it has perhaps helped at the margins but has failed to come anywhere close to replacing the robust industrial economy that came before it.”¹

St. Joseph County’s population growth and South Bend’s less severe population decline can be partly attributed to the “Eds and Meds” economy. It is significant that Segedy identifies Youngstown and Flint as two cities where this dynamic did little to stop population and economic collapse.

South Bend is not a college town. We are too large and diverse a community to be characterized by such a label. Our history of manufacturing and continued reliance on broad economic forces puts South Bend into an entirely different category than a college town. However, this is not to say that the multiple local colleges in and around South Bend have not helped soften our population decline and avoid the fate of Gary, Flint, and Youngstown.

The University of Notre Dame has not factored largely in the More People story. This is because the campus does not reside in the South Bend city limits. From a population standpoint, Notre Dame has historically had little direct impact on the population count of South Bend. In recent years, this has begun to change with the development of Eddy Street Commons and the university’s investment in the neighborhood immediately to the south of campus that resides in city limits. While the residential campus is not in South Bend, more and more land in South Bend is owned by the university.

However, to most Americans, their knowledge of South Bend may be limited to the large private institution just north of the city and its world-famed football team. Our story has largely focused on the years of 1960 – 2010, when South Bend experienced population and industrial collapse. During this same time period, the University of Notre Dame continued to grow from a small private university with a famous football team to a larger and more research-based university (with a famous football team).

Notre Dame’s growth over the last half century has not been the only local higher education institution to experience growth. Indiana University South Bend (IUSB) – which does lie in the city limits – as well as Saint Mary’s College, Holy Cross College, Bethel University and Ivy Tech Community College have grown as well. This growth of higher education institutions in or bordering South Bend city limits helped cushion the blow of deindustrialization. IUSB encapsulates this trend as land that used to be the site of the South Bend Watch factory is now part of the campus.

South Bend Watch Factory along Mishawaka Avenue from a 1910 Postcard.

Indiana University of South Bend Administration Building on the site of the old South Bend Watch Factory. IUSB.

Furthermore, South Bend has also doubled down on medical institutions as well. While the city infamously lost St. Joseph Medical Center in the early 2010s to neighboring Mishawaka, due to the presence of Beacon Medical Group, South Bend Medical Foundation, and South Bend Clinic, South Bend still is unequivocally the medical hub of St. Joseph County and the larger Michiana area.

The massive Beacon Medical facilities and South Bend Medical Foundation facilities just north of downtown South Bend. 2019.

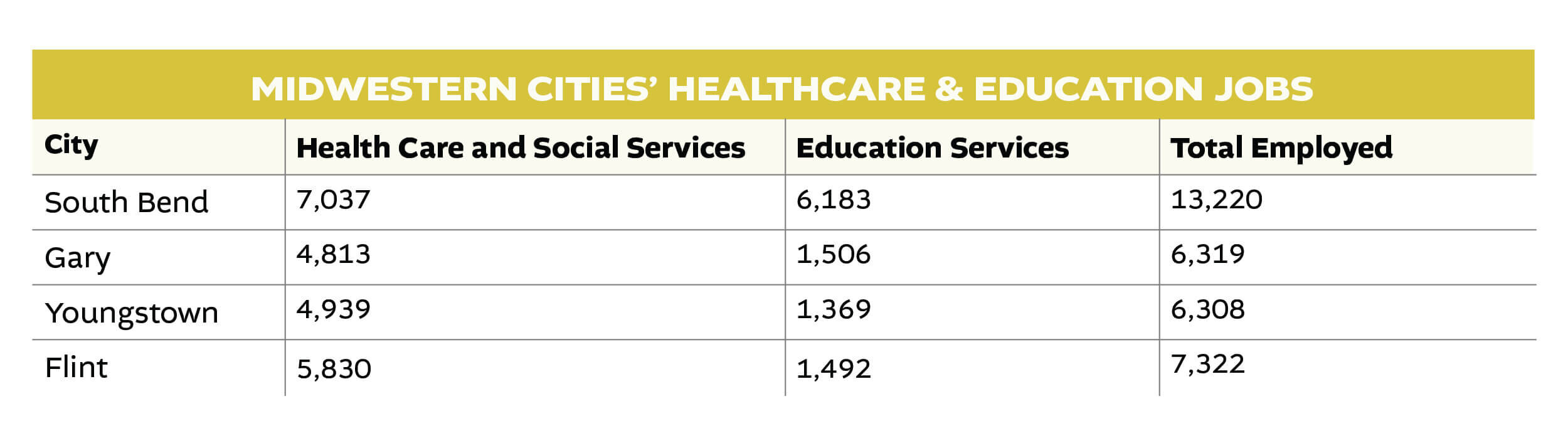

South Bend’s moderate success in growing successful educational and medical institutions lessened the economic blow of deindustrialization and paid dividends for stabilizing the city’s population. See the numbers below of city residents employed in health care and education services in South Bend and in the three Rust Belt cities in our analysis hurt most by population decline. Note these residents are employed in these fields regardless of whether that job is in the primary city or not.

The three other cities all had higher populations than South Bend at their peak. Due to a variety of reasons, the “Eds and Meds” sectors grew in South Bend, helping provide jobs to city residents and maintaining South Bend as a job hub for the metro region. These new jobs have helped soften the blow for South Bend that devastated other Rust Belt cities. The city would have been even more successful if it would have managed to keep all those employed in South Bend living in the city limits, but we can see in the above chart how South Bend’s higher education and medical institutions provided a stable and growing workforce for the city.

Reason Four: South Bend remained a destination for new immigrants

South Bend – like so many American cities – depends upon immigration to survive. Through the course of her history, the city experienced waves of newly arrived immigrants looking for opportunities. These new immigrants – my Hungarian great-grandfather in 1907 among them – usually concentrated in certain neighborhoods for the first two generations before dispersing throughout the larger community.

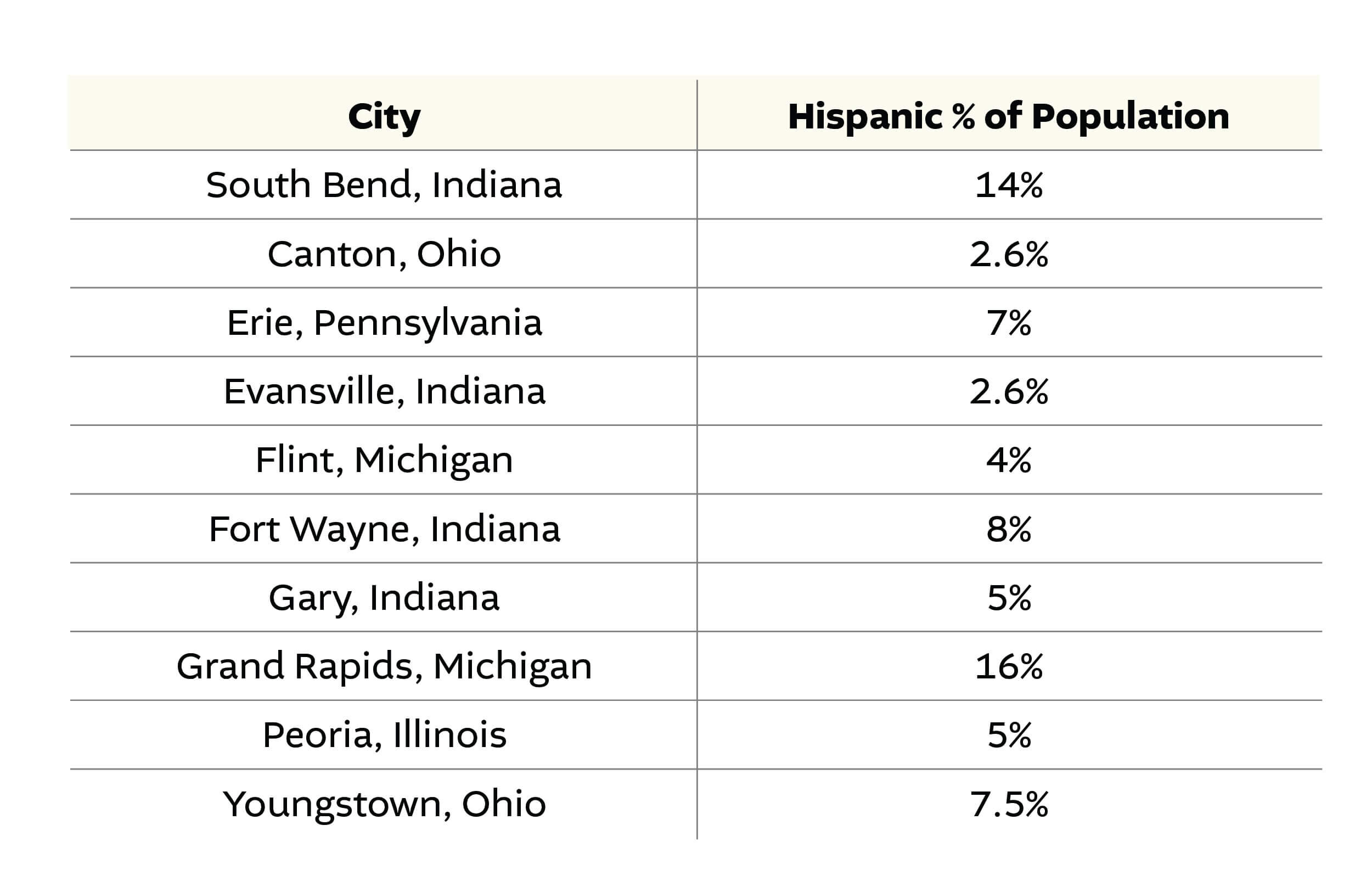

Starting in the 1960s, immigrants from Central and South America became a primary source of immigration growth in the United States. South Bend relied on immigration to help soften the blow of white residents leaving the city limits for nearby suburbs. In 2010, the Hispanic population, as defined by the Census Bureau, made up 13% of South Bend’s population. In the 40 years from 1970 to 2010, South Bend’s Hispanic population increased 627% while its white population dropped by nearly 50%. South Bend remained the primary point of entry for immigrants into St. Joseph County, with 67% of all Hispanic St. Joseph County residents living in South Bend.

South Bend stands out in its ability to attract new Hispanic populations into its city boundaries. The city has the second highest share of Hispanic populations among the 10 peer cities.

Unlike most other Rust Belt cities of its size, South Bend continued attracting new immigrants to the city. The cities which suffered the worst population decline – Gary, Flint, Youngstown – all have struggled to do the same.

South Bend’s success benefitted from the Catholic Church structure already in place that helped attract and retain Hispanic immigrants. Between the University of Notre Dame and the dozen nearby small Catholic parishes and schools dotted across South Bend, the city was ripe to welcome a new wave of tightly knitted immigrant groups who happened to share the faith of most of the former immigrant groups.

My own Catholic parish growing up, Our Lady of Hungary, founded by Hungarian immigrants in the early 1920s, has been a cultural starting point for new Hispanic immigrants. Growing up in the parish in the 1990s and early 2000s, the number of parishioners had been shrinking decade after decade. When my father attended the school there in the 1960s, nearly 500 children were enrolled. By the time I graduated in 2006, school enrollment was under 100 students.

The parish actively sought new Hispanic immigrant families and saw success. A new parish priest was welcomed who began giving Mass in Spanish as well as English. Church attendance, as well as school attendance, rose. A decade or two ago, it was almost a foregone conclusion Our Lady of Hungary would close the school and the parish would soon follow. Just like South Bend as a whole, new Hispanic immigrants helped cushion the parish’s loss.

Hispanic population growth on the city’s west side has helped soften the blow of population decline in other demographics. Photo - @SmartStreetsSB

Reason Five: City investment

The last reason we will explore as to why South Bend survived her population collapse is far more ethereal than most topics analyzed in More People. I have no census figures or employment numbers to back up this final reason, but there is a need to give credit to the two generations who helped shepherd our city through such tumultuous times. The City – both elected officials, government employees, and civic leaders – proposed large, and sometimes controversial, measures to stem South Bend’s economic and demographic collapse. There were certainly some failures – the College Football Hall of Fame most noteworthy among them – but the successes equally outweigh the failures.

Civic leaders did not merely attempt to manage South Bend’s decline, they actively sought to reverse it. Throughout the past half-decade, there has been a conscious effort not just to maintain what remained of South Bend, but to grow. The city developed reasons for residents, both old and new, to come and stay.

The city turned to the river from which the name South Bend comes, installing the first man-made whitewater rafting course in North America along a former industrial river raceway and establishing the South Bend River Lights as a public monument unique to South Bend’s river and people.

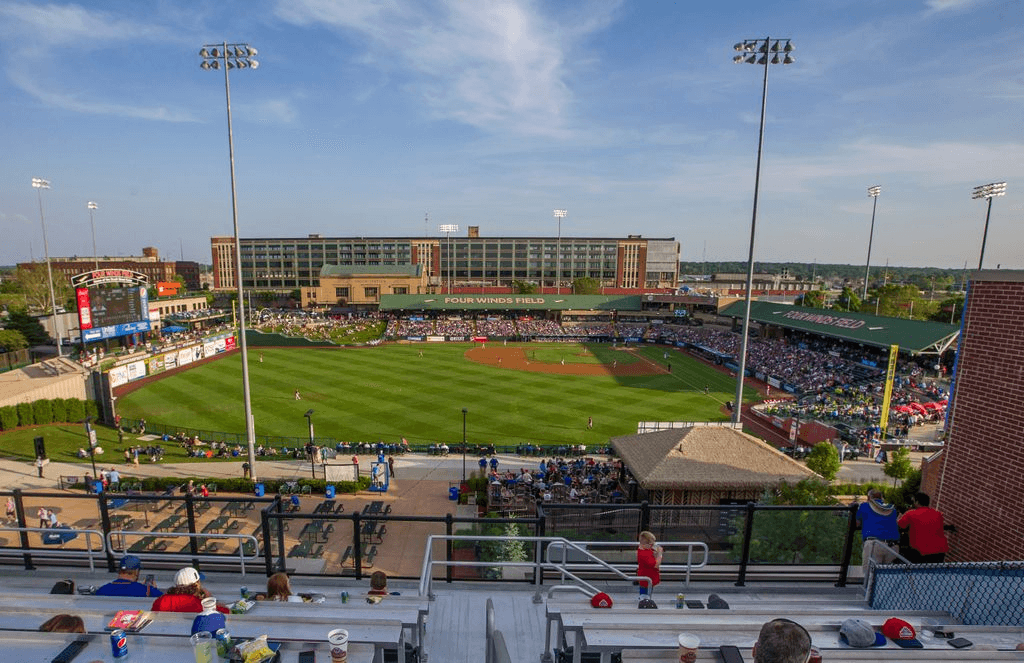

South Bend was the second city in America to return baseball parks to urban locations with the city-led construction of Coveleski Stadium in downtown South Bend, now home to the South Bend Cubs.

The relationship between the city’s hinterland and the city proper has helped foster one of the largest and oldest farmer’s markets in the Midwest.

Leaders also built upon the civic foundation of the city by investing and growing Potawatomi Zoo, the oldest zoo in Indiana.

Just recently the city – with nearly two-thirds of funding coming from private local sources – renovated and expanded all existing parks facilities and trails. The people of South Bend have access to some of the best outdoor public spaces in the nation.

Four Winds Field at Coveleski Stadium nestled downtown in the shadow of a former Studebaker Building. The second ballpark in America built in the Urban Renaissance tradition. Photo Credit South Bend Cubs.

The city has reinvested in all its public spaces – not just parks – with the belief that urban centers should be urban in nature. The restoration of Western Avenue, seen in the above picture about Hispanic population, demonstrated the understanding that the city needed to invest in its neighborhoods once again. The results have been a steady growth of local, small-scale investments back into those very neighborhoods.

How much did those – and many more – initiatives impact South Bend’s population? I don’t know. Did the other nine cities listed above engage in similar projects? I am sure they did. But just because something is not easily measured does not mean it did not matter. South Bend civic leaders did not abandon their city and the city survived.

Conclusion

Many of the reasons listed above are all interconnected. South Bend remained a destination for new immigrants because South Bend remained a job hub for the area. South Bend remained a job hub partially because of the growth in the “Eds and Meds” sector, which helped St. Joseph County avoid population collapse and inspired city leaders to reinvent old spaces for new purposes. Trying to parse out which was the chicken and which the egg can cloud the overall story. South Bend managed to weather the massive headwinds – suburbanization, deindustrialization, declining population size, racial tensions between the diverse city and the hinterlands, federal programs aimed at disinvestment in the city – well enough to remain in a prime position to see growth once again in the 21st century.

This was not inevitable. Just as South Bend’s population decline was the result of a series of policy and cultural choices, South Bend’s survival was the result of thousands upon thousands of individual decisions made by city leaders and residents. Just as our decline should be examined and mourned, our survival in the face of overwhelming odds needs to be analyzed and celebrated.

. . .

What began as a hope to discover old articles on the 1970 Census has morphed into a seven-part article series on my hometown. I could never have imagined back in the early summer that so many thousands of people would read, comment, argue, and enjoy South Bend’s story. The story has resonated not just with those who are intimately connected to this beautiful city, but also with those with no connections to South Bend. This city can act as a mirror – clouded and distant – onto the legacy of America.

In South Bend’s struggle we learn so much about America. There is not a single transformational trend that has impacted America in the past century without also impacting South Bend. Sometimes, in order to understand the larger picture, it is necessary to dive into the little details. My city is a little detail. I have attempted to tell this story to the best of my ability, using hard facts to explain what happened here over the past half century. But South Bend’s story is not over. We are not a museum artifact to be analyzed as a fixture of the past. Instead South Bend is home to thousands of good, active, and living people.

This coming Spring, the results of the 2020 Census will give us a glimpse of the past decade of South Bend’s story. I believe and hope that 2010 will be the bottom of our long slow decline and 2020 marks the beginning of something both old and new: more people in South Bend.

A few days ago, I took my son to watch the new hydroelectric power plant being constructed in downtown South Bend. The city once again turns toward the river. My son is the fifth generation of the Molnar line to call this city home, stretching back over a century now, and it will be his city to love, enjoy, criticize, and engage. Time will tell what his South Bend will look like, but I will keep watching – and writing about – this city I love, a little less blindly now, as we work toward her future.

Me and my son – fourth and fifth generation sons of South Bend – watching the new power plant being constructed under what will become the new Seitz Park.