More People: The Great Annexation War of South Bend and Her Suburbs

This is the introduction to an article and podcast series by Joe Molnar titled More People: How South Bend Lost 50,000 People in 50 Years. Joe is a proud 4th generation son of South Bend.

Read the original series: Introduction | One | Two | Three | Four | Five | Six | Seven

Read the census recap: Introduction | One | Two

Subscribe to the podcast: Apple | Spotify | Google | Stitcher | TuneIn

1919 Liberty Loan Parade in downtown South Bend led by a tank manufactured locally by Oliver Chilled Plow Works.

“Since the argument that ‘we are all part of one county’ will never fly, the immediate city problem is survival. This may well involve the recognition that city and suburbs are like separate nations…. Since American cities are ‘unwalled’ and no tariffs are in place, foreigners (suburbanites) are free to enter and to exploit city resources.”

– Frank X. Steggert. Letter to the Editor, South Bend Tribune, March 29, 1993

• • •

How is a city supposed to grow?

A war was waged over this question in the early 1990s. Not a war with guns or cannons, but with speeches, articles, court cases, and state enforced laws. Though no lives were lost, hundreds of thousands of lives were changed by the outcome.

This war tore St. Joseph County into roughly two camps. The first is represented by the cities of South Bend and Mishawaka. The second by residents who resided in unincorporated land in St. Joseph County, county government officials, and Indiana State Representatives and Senators.

The war was the culmination of a decades long struggle between the City of South Bend and its hinterlands. For five decades, beginning in the 1940s, the area surrounding South Bend – and to a lesser extent Mishawaka – began to develop at urban densities, but actively fought efforts to be annexed into either city limits. South Bend attempted large scale annexations throughout the 1960s and 70s, but these were defeated, usually in court, at the behest of county residents. By the early 1990s, the city was facing a crossroads as the city population continued to decline and the number of households barely inched upwards. South Bend shrank while its suburbs boomed.

These new suburbs would not exist without the cities of South Bend and Mishawaka. The cities provided jobs, medical care, the airport, zoo, retail districts, factories and warehouses, public spaces and parks, and restaurants—amenities available to all residents regardless of where they lived. Without these amenities and the wealth generated, newly developed subdivisions outside of the cities would not have existed. However, unincorporated suburbs refused to join with the city that they depended on for their survival.

As previously discussed, while South Bend began its half-century long population decline, the entirety of St. Joseph County continued to gain residents. South Bend’s decline was not the result of the region losing people, but specific movement of populations within the region. Most of this growth happened in unincorporated St. Joseph County. The growth of a metro area while its primary city stagnates or declines is an unprecedented outcome now taken for granted.

South Bend knew it had a problem on its hands. As we have shown in the previous article regarding jobs, the city remained the prime employment hub in St. Joseph County. South Bend needed to turn the tide and increase its population if it was to afford to provide services to the people of St. Joseph County – both residents and non-residents of the city.

With this dilemma in mind, Mayor Joseph Kernan in late 1989 established the Mayor’s Housing Forum in an effort to identify the ways the city could bolster the housing stock in the city for low- and moderate-income residents.¹ The Forum made four recommendations to the Mayor, the most substantial and controversial being that the city should begin an aggressive and massive annexation effort to make land available for new housing and to lessen property tax burdens on current residents.²

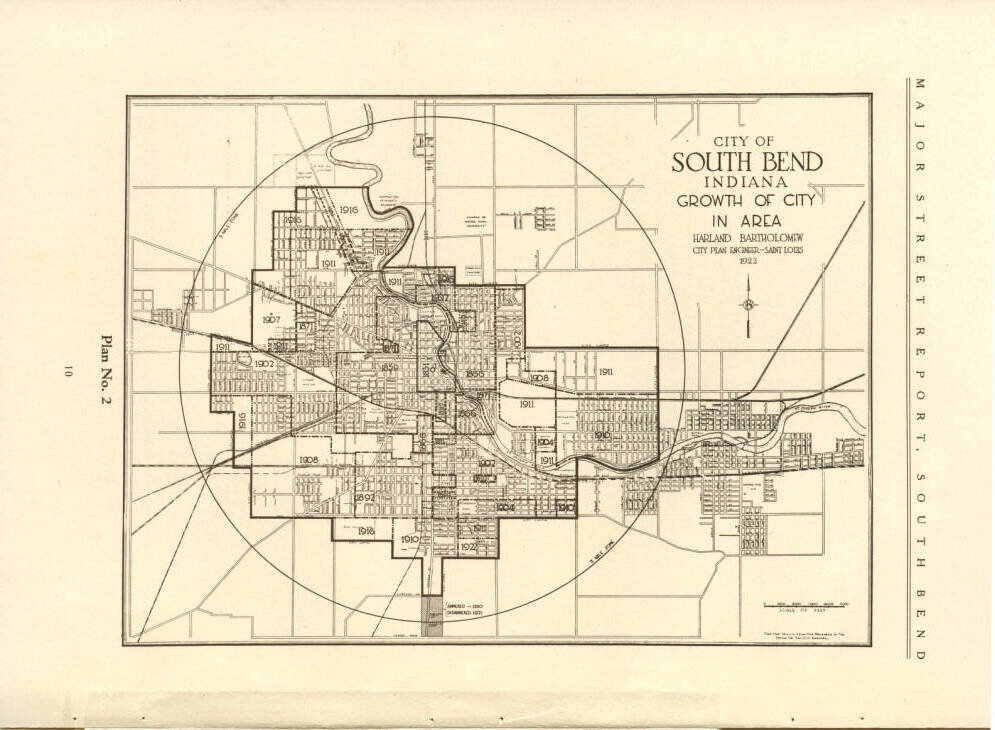

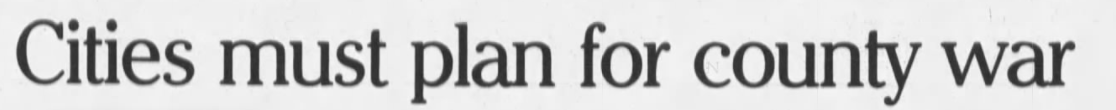

From this recommendation came the Annexation Policy and Plan for City of South Bend. This plan recommended large-scale annexations which, if all enacted, would have doubled the size of the city, and would have included the annexations of most of Clay Township, the University of Notre Dame, and Saint Mary’s College.

This was the spark which began the war. The city began to fight back against decades of wealth leaving the city for land just outside its borders. The war between the city and its hinterlands eventually found its way to the Indiana Statehouse, which implemented a legally dubious law limiting annexations for cities within St. Joseph County at the behest of representatives of South Bend’s premier suburb Granger.³ This law did not apply to any other counties in the state.

Prior to the rise of the automobile, annexations in St. Joseph County were largely non-controversial and mostly amicable. To understand why South Bend lost tens of thousands of residents, we must understand why those residents did not flee to Florida or Arizona, but instead settled right across the city borders.

This article will explore the history of South Bend annexations, beginning all the way back in the 1830s, and will help to explain how a simple process devolved into a full-scale war between South Bend and the suburbs.

The article will be broken up into three parts to better frame how the narrative around annexations changed throughout South Bend’s history.

Urban Growth, 1840 – 1920

Urban and Suburban Growth, 1920 - 1960

Urban and Suburban Conflict, 1960 - 2010

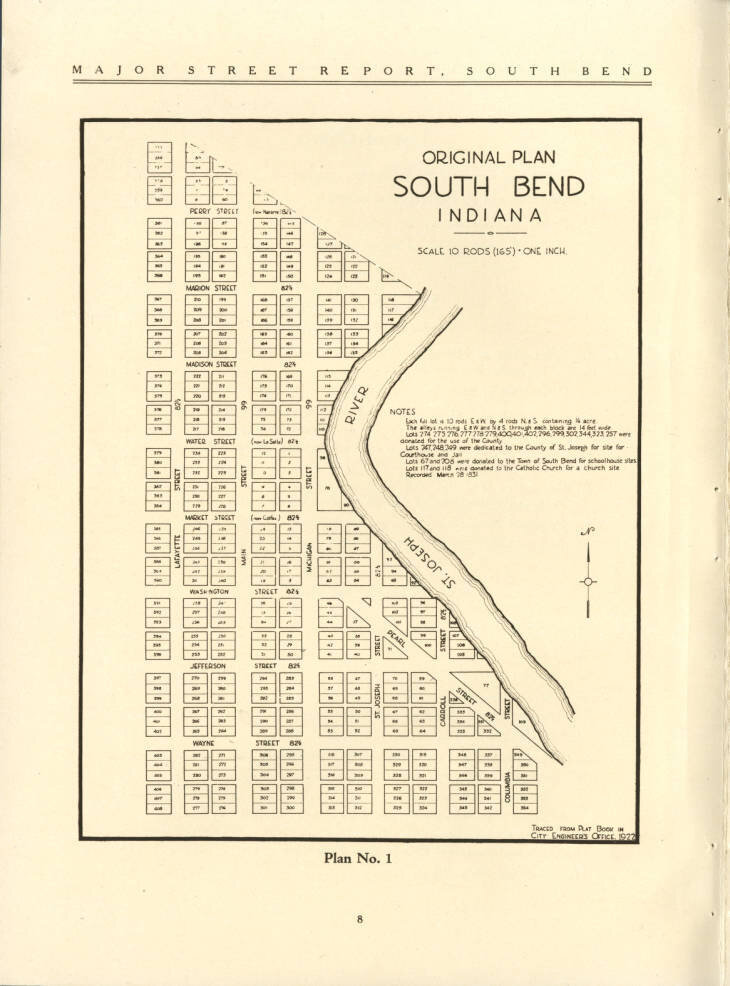

Original Plan South Bend Indiana 1831. Traced from Plat Book in City Engineers Office in 1922.

Part One: Urban Growth, 1840 - 1920

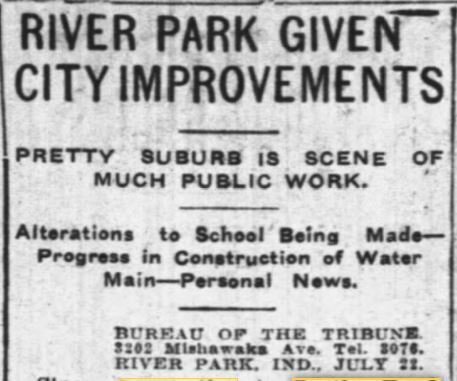

South Bend has grown from a small town of 128 inhabitants in 1831 to a thriving and progressive city of approximately 71,000…Coincident with the gradual increase in population, South Bend has from time to time annexed additional areas until it has grown from an area of approximately one-quarter square mile in the original town to its present areas of 15.74.”

– Major Streets: Present and Proposed Report, 1924

Before suburbanization, housing sprawl, and the rise of the automobile-obsessed development pattern, a metro area and its primary urban space rose and fell together. Cities grew and changed in this way throughout history, dating back to the first cities over 8,000 years ago. A city and its hinterlands were co-dependent upon each other. On average, the city provided the hinterlands with a large market to sell wares and food while the hinterlands provided the primary city with food and a continual source of migration of workers leaving farms for jobs in the city.

When South Bend was first platted in the early 1830s, the development pattern reflected the country as a whole. At the time the United States was 91% rural and 9% urban.⁴ Dotted across the country – although more substantial in the Northeast – small cities popped up. Dense urban spaces were surrounded by rural countryside immediately beyond the city borders. As cities grew in population and economic activity, they grew outwards and slowly acquired more land. When annexations of land occurred adjacent to the city boundaries, the farmland would be subdivided into city plots and connected to the existing infrastructure network.

This growth aided rural residents in the countryside as it provided a larger marketplace to sell wares and farm goods, while providing the city a larger area to grow. There were no suburbs during these years – although the largest metropolises like New York City started to see “Railroad Suburbs” spring up during the middle of the 19th century. People were either in the city limits or were rural residents most likely tied to an agriculture-centered profession.⁵

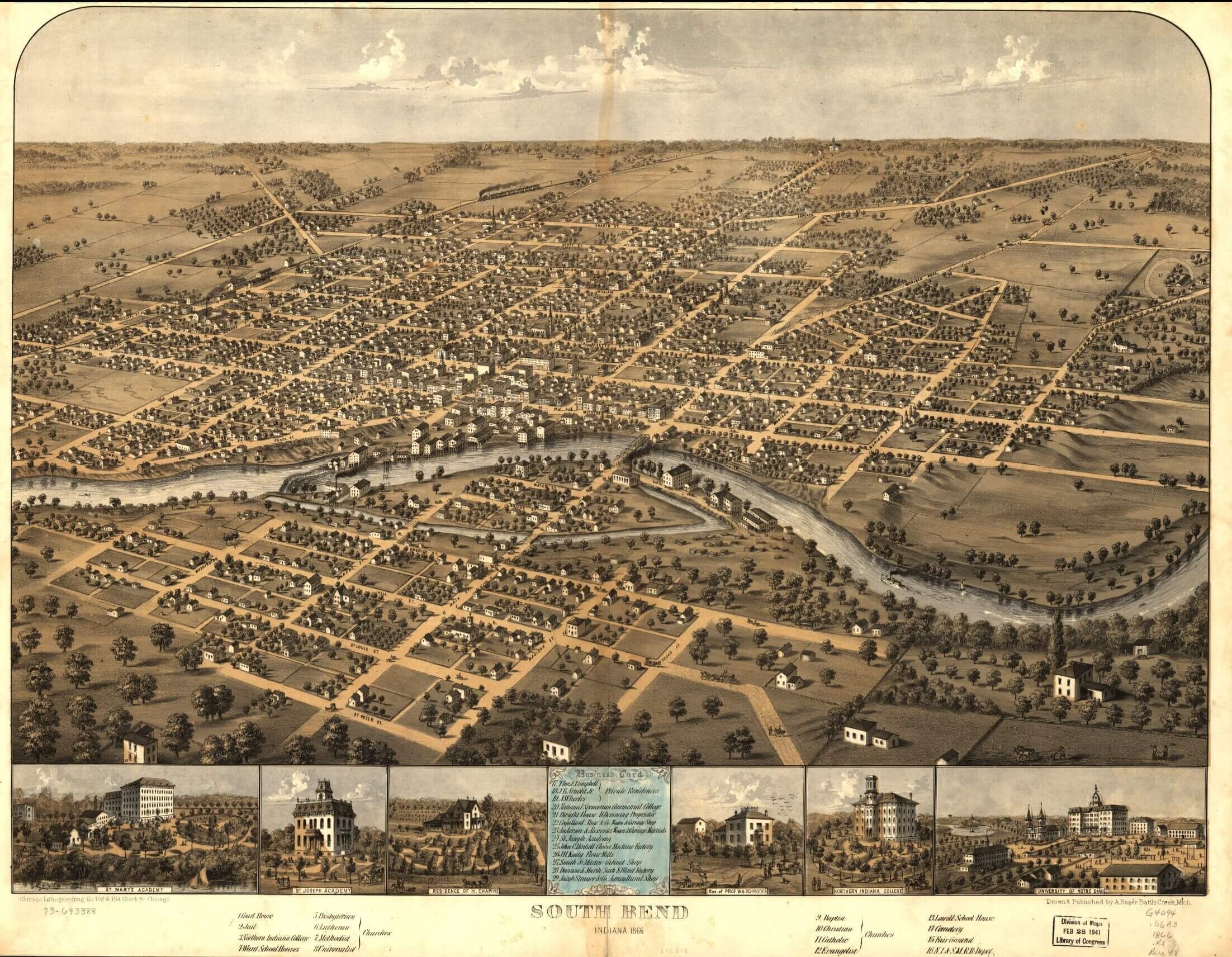

South Bend in 1866, Library of Congress. Note how immediately after South Bend city limits end the rural countryside begin.

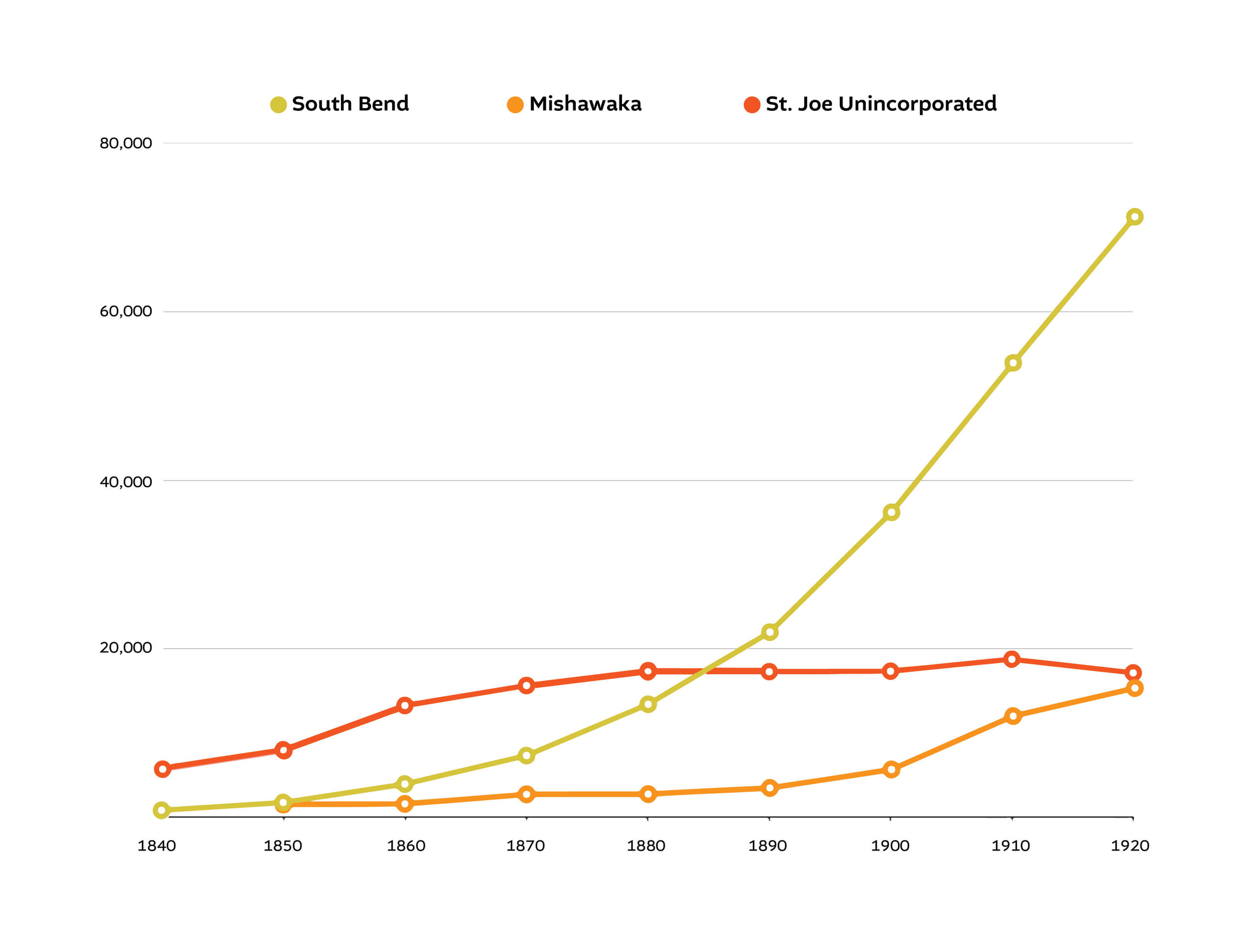

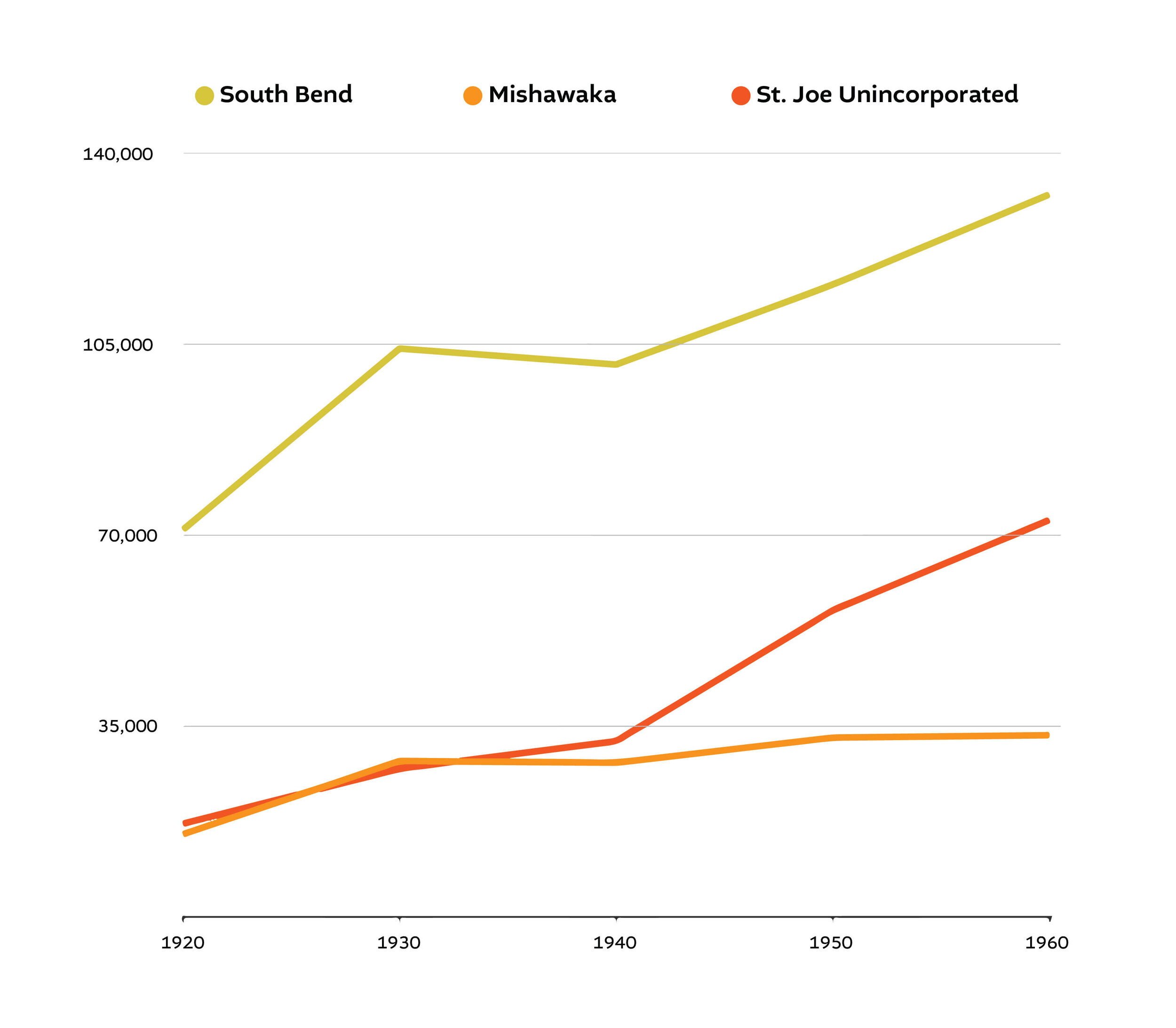

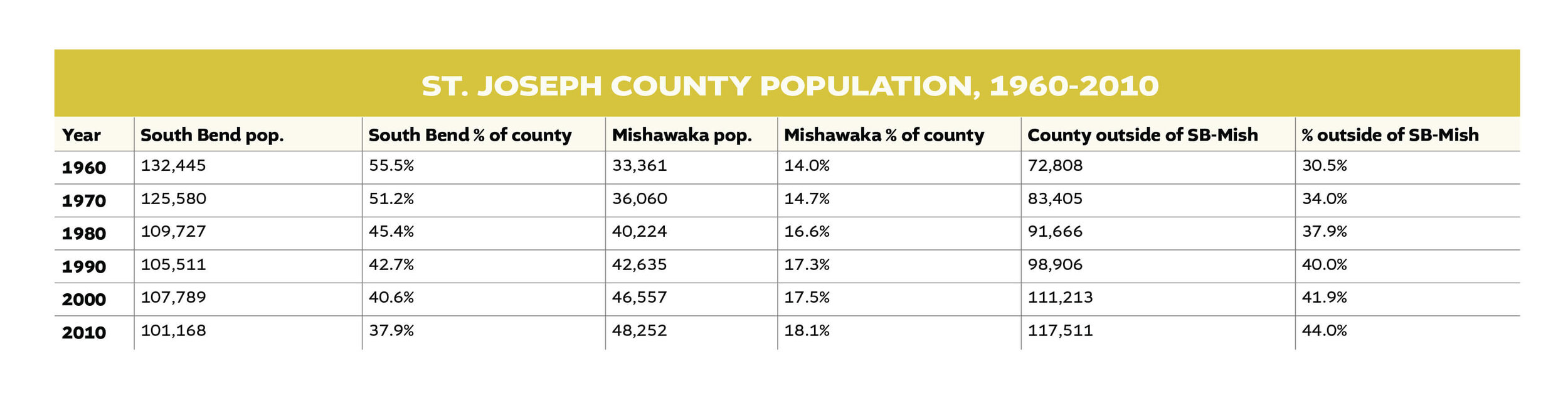

The below chart tracks the first century of growth in South Bend, Mishawaka, and the remaining areas in St. Joseph County. A few years after South Bend’s founding in 1831, St. Joseph County matched the country, 90% of residents within St. Joseph County lived outside the cities and a little over 10% lived in the cities.

As South Bend – and to a lesser extent Mishawaka – grew in the second half of the 19th century, the remaining population of St. Joseph County remained essentially flat. From 1860 to 1920, the population outside of the city limits rose from 13,135 to 17,126, or about 30%. In comparison, South Bend’s population went from 3,832 to 70,983, or a gain of 1,852%, in the same time frame. South Bend grew from just over 11% of St. Joseph County’s population to nearly 69%.

How did this growth happen? It was not that the original plat of South Bend – shown in the picture above – became a Manhattan-like metropolis. Rather as the urban population of the city grew, demand for housing grew with it. South Bend’s outward growth came from two different types of annexations. The first was annexation of farmland or vacant fields with the owner’s eager acceptance. The majority of annexations were of this type, and many times, these lands were owned by prominent citizens of South Bend. For example, below is a statement by a Mishawaka resident who actively sought South Bend annexation.

I am in favor of annexation principally for commercial advantage. It is a well known fact that South Bend is known all over the United States, and, in fact, all over the world, and is the best advertised city of its size in the United States.

– M. V. Beiger, South Bend Tribune, May 28, 1903

Annexation was once a simple process: South Bend’s Common Council would pass an ordinance adjusting the city boundary lines to include the desired territory, and once the mayor signed the ordinance, the new boundaries were established. Per Indiana law, by the 1950s the city would have had to demonstrate how it would provide city services to the annexed area within a reasonable time frame.⁶ This process gave South Bend the ability to grow incrementally outward as the urban population rose. The residents and owners of the annexed area could sue the city if they believed the city could not provide adequate services.

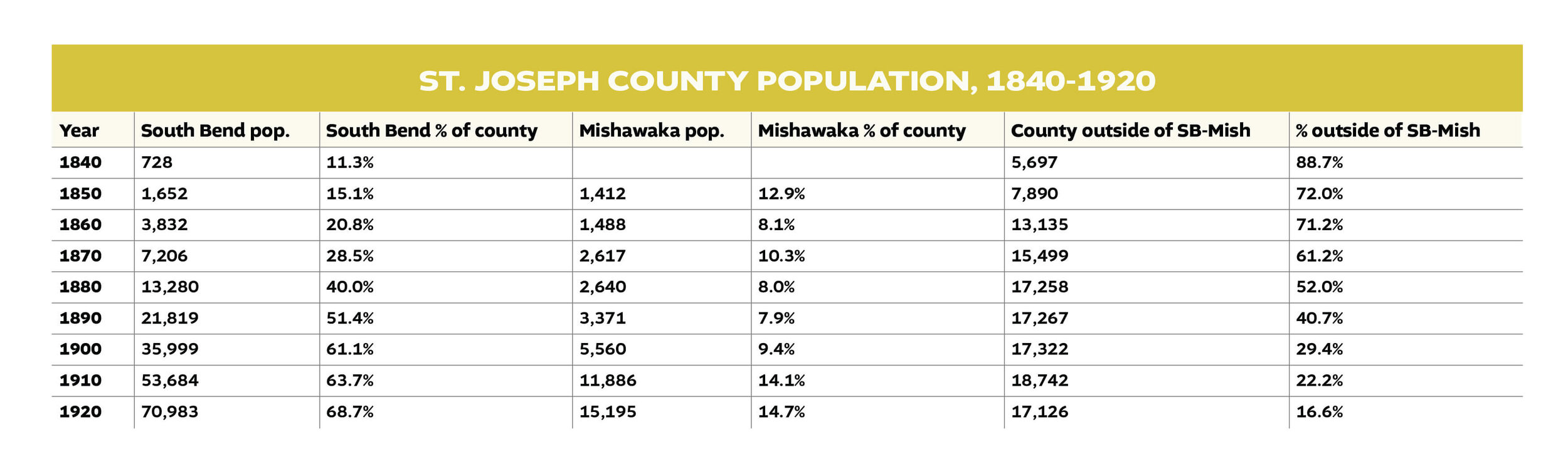

The second type of annexations were when South Bend merged with already existing towns. The first took place in 1867 when Lowell – present day East Bank Neighborhood – merged with South Bend. The second occurred in 1892 when South Bend absorbed Myler Town – present day Indiana Avenue immediately south of Ignition Park – through a process of both South Bend and Myler Town holding an election to determine the issue.⁷ The third was South Bend’s annexation of River Park in 1911. Like Myler Town, the residents of River Park held a vote and the vast majority chose to join South Bend.

Just a few months after being annexed into South Bend, River Park began seeing the benefits of the merger. SBT 7-22-1911.

I have scoured the South Bend Tribune archives during this period and read countless articles about the annexations mentioned above as well as multiple other small annexations detailed in the below map. Rarely – if ever – did the owners of annexed property object. More often, South Bend officials tended to have doubts that the annexed area would pay enough taxes to support its cost. In the case of River Park, for example, the South Bend City Council initially denied the annexation of River Park for fears that it was too costly an endeavor.

While South Bend’s population rose, the unincorporated population of St. Joseph County remained relatively flat from 1880 to 1920. Considering nearly all residential properties in unincorporated St. Joseph County were farmsteads, the population plateaued because the county could only support so many independent farmers. Once that limit was met around 1880, there was inevitably little population growth outside of the cities after that point.

By the beginning of the 1920s, St. Joseph County had been fully transformed from a rural farming county with a small urban area at its heart to a largely urban county surrounded by sparsely populated farmland. Geographically, South Bend made up less than 5% of the total land area for St. Joseph County. However, nearly 70% of all St. Joseph County residents resided in South Bend. While 1920 was still 40 years and 50,000 people away from South Bend’s peak population, that year would prove to be South Bend’s highest share of St. Joseph County residents living within its own boundaries.

Annexation map of South Bend, 1922

Part 2: Urban and Suburban Growth, 1920 -1960

“The answer to this problem is annexation, which is not always popular with the property owners to be taken in the city because these suburbanites do not want to help pay for what they are receiving from the city at no cost to them…They enjoy and share every benefit the city has to offer yet they contribute nothing to its support. They travel and wear out city streets, which were built and paid for by city taxpayers. They work in our factories, shops, stores, and office buildings…For all practical purposes they reside inside the city yet they pay no city tax nor do they in any way help to pay the cost of furnishing these services.”

– William S. Moore, former South Bend City Engineer, South Bend Tribune, June 27, 1954

In the 1920s, the growth pattern which had existed since South Bend’s founding began to shift. Starting in 1920, the unincorporated portions of St. Joseph County’s population growth rate began to increase faster than South Bend and Mishawaka. While the two cities continued to grow, the rest of the county’s population increased at a faster rate. As the charts below indicate, South Bend dropped from nearly 69% of the total county population in 1920 to 55.5% in 1960. This drop was entirely due to the rise of the population of people living on unincorporated land, which grew from 17,126 in 1920 to 72,808 in 1960. This growth exceeded both South Bend and Mishawaka’s.

What spurred this rapid unincorporated population growth in the 1920s? In one simple explanation: the car. Due to the automobile becoming more and more widely available, people had the opportunity to live farther from where they worked. This trend of living in larger lots away from the city – but still fully working, shopping, and dining in the city – exploded after World War II. This massive growth of unincorporated suburbs after World War II began to have negative consequences for the city and the entire region. South Bend continued to grow during the next forty years largely through fully developing the remaining open land left in the city limits – Edison Park, for example – and small scale annexations on the south side of the city.

South Bend’s continued growth in the 1940s and 1950s helped hide the massive suburbanization taking place in St. Joseph County. In those two decades, the share of St. Joseph County residents living in neither of the two primary cities rose from 19.9% to 30.5%. This is a crucial time span for understanding South Bend’s later collapse in population. Because South Bend – and Mishawaka – allowed subdivisions to develop in the 1940s and 1950s at near urban densities outside of the city limits, the chances of these lands ever joining the city dropped significantly.

Prior to the automobile and suburban growth, the city would typically annex a portion of land on its borders – usually at the behest of the owner or developer – who then would subdivide the land. After World War II, a developer would often subdivide and develop land without ever annexing it into the city limits. Once these plots were established and houses were built under lower (cheaper for the developer) standards, the owners of these new houses would rarely welcome annexation into the city.

Typical 1940s and 1950s neighborhood in unincorporated Clay Township. Notice the lack of sidewalks and other typical public amenities found in city neighborhoods. This was cheaper for developers.

What were some incentives for developers to subdivide and build housing without annexing into the city limits? Below are a few examples:

St. Joseph County soil is generally suitable for private well and septic systems.

Indiana state law governing well and septic systems had few difficult standards to meet.

Developing subdivisions in the county was cheaper. No need for sidewalks, street lights, sewer, and water lines or fire hydrants. All savings that could be split between the developer and the future homeowners.

No county-wide growth management plan was ever developed. Such a plan may have recognized the costs of haphazard land development.

Property taxes were cheaper by a factor of 2 or 3 in the county and the same house built in the county was cheaper to own than in the city. Developers used this as an incentive not to annex their subdivisions.

The Federal Housing Authority (FHA) would only insure mortgages if the subdivisions were guaranteed to be segregated. This was easier to accomplish in the county than the city where neighborhoods were more integrated.

By the 1950s, large suburban growth was already becoming a point of conflict between the city and its hinterlands. Starting in the 1940s, we first find articles and letters in the South Bend Tribune regarding unincorporated residents pushing back against annexations. In fact, the group, Hoosier Suburbia, formed in Centre Township to fight annexations in St. Joseph County and developed into a statewide organization. In 1959, the group opposed an annexation of 65 acres of land in Clay Township. Those opposing the annexation did not even live in the annexation area.

Those in opposition claimed that land in the city could be subdivided into smaller plots and developers only wanted to maximize value, discounting the fact that city development standards were more onerous and expensive than unincorporated standards. This was the beginning of a half-century of annexations being forcefully opposed by unincorporated residents, even if they did not live in the target area.

South Bend Tribune 03-06-1959

Remember, these new suburbs were, for all intents and purposes, part of the urban fabric of South Bend, especially those first subdivisions established in the 1940s and 1950s. Everyone within the urbanized area – incorporated or not – benefited from the central city. However, because these neighborhoods were cheaper to build, developers were incentivized to not annex into the city which had higher development standards. Once the homes were built and occupied, residents paid cheaper property taxes whiles receiving nearly all of the benefits city residents held. That incentive structure was maintained and fought for.

Part 3: Urban and Suburban Conflict, 1960 – 2010

“If you took South Bend away, Clay Township would not exist.”

– Bruce Hudson, South Bend Tribune, Nov. 20, 1992

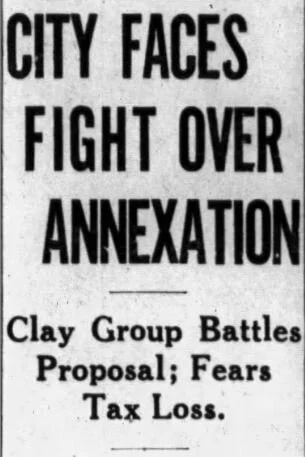

The 1960s began a half century long decline in South Bend’s population. As the below chart indicates, the number of St. Joseph County residents who lived in South Bend continued to plummet each decade, while the share of the population in unincorporated areas rose and eventually surpassed that of South Bend.

This was and continues to be a huge problem. Losing population in and of itself was bad, but losing population while still expecting to provide quality urban services for a growing county was even more difficult. For example, below is a list of institutions that benefit the entire county regardless of residence and are in some form subsidized by city taxpayers:

Four Winds Field at Coveleski Stadium

Morris Performing Arts Center

The Parks and Trails System of South Bend, including amenities like the East Race and Howard Park Ice Trail

The Century Center

Potawatomi Zoo

South Bend International Airport

Most of these facilities were built under the city’s bonding authority and backed by taxpaying city residents. While some of the facilities are no longer directly subsidized by the city of South Bend General Fund, they would not exist if not for city taxpayers. Facilities and institutions below receive indirect subsidies from city residents:

Indiana University South Bend

Memorial Hospital

South Bend Clinic

Ivy Tech South Bend

St. Joseph County Court Houses

St. Joseph County Jail

County-City Building

South Bend Farmers Market

St. Joseph County Public Libraries

Center for the Homeless

The above entities generally do not receive direct city tax dollars; however, all are non-profits or government-based institutions which do not pay property taxes. These are rather large complexes and the roads surrounding them still need to be paved, maintained, and rebuilt periodically. That investment is a direct subsidy from South Bend taxpayers to land which does not produce any revenue. In the case of the larger institutions like Indiana University of South Bend, the campus is on prime river-adjacent real estate. Not only is the indirect subsidy in the form of roads to and from these locations but the loss of potential revenue if they were in the private sector.

Both sets of entities are public goods. That is, even if residents in St. Joseph County never use one of them, the area is better because they exist. For instance, county residents have a better quality of life because of a functioning health care system. Even if you are never rushed to the emergency room, someone you know probably will be. Even though you may never need the court systems, our society could not exist without it. The existence of the airport, parks system, and zoo is a public good users and non-users benefit from.

This is not to say that any of the above entities are negatives because they exist in the city. Many of the institutions mentioned provide thousands of jobs and help make South Bend a great place to call home. The point of the exercise is to demonstrate that city residents pay directly or indirectly for entities and services that all county residents use or at least benefit from. The 1992 Annexation Report published by the city stated:

Although open to and enjoyed by all residents of St. Joseph County, only those residents who live within the City limits bear the burden of the tax levies and the yearly maintenance of these first-class facilities. Large numbers of suburban residents utilize a significant portion of the City’s resources and services on a daily basis. Those residents who commute into and work in the City use the City’s streets, traffic control systems, sewer and water service, and various other public facilities. Non-city residents while doing business in the City, also have available to them police, fire, and medical response teams if required.

In the last article, we explored how nearly three out of every four people employed within the South Bend city limits do not live in the city. Those approximately 45,000 people enter South Bend every day and do business without contributing to the maintenance of the services their jobs require. This is why population decline – and, just as importantly, population movement within the same metropolitan region – matters.

This is further compounded by the fact that city residents still continue to pay county property taxes for the few county services they benefit from – County parks, for example – but also pay for services that only county residents benefit from such as the beleaguered leaf-pickup operation for unincorporated residents. Leaf-pickup is just one of the latest examples of city residents directly subsidizing county services and receiving zero benefit. The term ‘exploitation’ is not out of the question under the current tax regime arrangement.

As South Bend shrank and the suburbs boomed, the city knew it had a problem. During the late 1960s and early 1970s – under Republican Mayor Lloyd Allen’s leadership – South Bend attempted a number of large-scale annexations; they all failed. This failure stagnated the city boundaries of South Bend for nearly two decades. During this time, suburban growth boomed, and the city captured little of it. This led to a crisis point in the early 1990s, when South Bend would fire the first shot of what became the great Annexation War.

By late 1992, the Annexation Policy and Plan for the city of South Bend was released and South Bend began making the smallest movements towards enacting its proposals. Right off the bat, Mayor Joseph Kernan denied that South Bend would pursue annexing the University of Notre Dame. City planners at the time indicated the return on investment would be minimal as the University is a tax-exempt institution. Instead, the first moves made were on the lowest hanging fruit, annexing land surrounded on all sides by the city. Just these moderate moves were enough to engulf the county in a war between South Bend and its hinterlands.

Map indicating all areas the Annexation Report identified as annexation targets.

In early 1993, after South Bend – and Mishawaka which also had large scale annexation plans of its own – began to discuss and begin the process of annexing suburban areas, State Representative Michael A. Dvorak of Granger introduced a bill in the state legislature which would severely limit all Indiana cities’ ability to annex land. According to the bill, a court must order an annexation not to take place if the following three criteria were met: the area already had adequate fire and police protection and road maintenance from a provider other than a city, the annexation would have a significant financial impact on the residents of the area, and if the annexation was opposed by more than 50% of the landowners or 75% of the assessed valuation area. The law made it impossible to annex areas other than small pockets of land at a time.

State lawmakers were lukewarm towards the bill – most of the people lawmakers represented lived in cities and would have been negatively impacted by the law – but Dvorak changed the bill to only affect St. Joseph County; an amendment was added that made the bill applicable to only counties in Indiana with a population between 200,000 and 300,000. St. Joseph County was the only county with such a population at the time. Mayor Robert Beutter of Mishawaka had this to say of the amendment:

“The bill is so extreme that it would not have a chance passing, because two-thirds of Indiana’s residents live in municipalities, and their state senators and representatives would protect their interests. But with the addition of the amendment, it could very well pass, because no one else in the state has any vested interest in the law. As a matter of fact, they should all be happy to vote for it, because it would put St. Joseph County at a significant competitive disadvantage with the other 91 Indiana counties.”

– Mishawaka Mayor Beutter, SBT, Feb. 21, 1993

The war between South Bend/Mishawaka and the hinterlands became so severe by 1993 that a state representative was willing to push a bill harmful only to St. Joseph County if it stopped the cities from annexing unincorporated residents. This tore at the social fabric of St. Joseph County.

In order to get a sense of the arguments made by both sides in the conflict, it’s best to let the people speak for themselves.

People against annexation:

“As residents of Clay Township have said before: We don’t want the city. We don’t need the city. Clay Township residents will fight and win the battle. We will not be annexed by South Bend.”

– Dolores Kuespert SBT, Dec. 6, 1992

“Those who live in South Bend or Mishawaka need to realize that the urban area, to those on the outside, looks like a sprawling metro-monster with high taxes, high crime and a big stack of problems.”

– SBT Editorial, Nov. 24, 1992

“I simply cannot afford South Bend’s grandiose schemes. Perhaps if South Bend were better managed, the citizens would not feel compelled to flee.”– Peggy Rossow, SBT Dec. 14, 1992

“For me, the economic issue is secondary. Sure, township residents do not relish the prospect of paying higher taxes that would be associated with annexation. The basis for rejecting annexation, however, is much more fundamental. We have made a choice concerning how we want to live and what type of government we want. That choice is to live in a more rural setting. That choice was county government and county services. That choice was not to live in South Bend.”– Richard G. Sheehan SBT April 14, 1993

People in support of annexation:

“Areas beyond the City limits have often developed as a legitimate response to the need for larger lot sizes or a more rural setting, or simply the availability of land. But they can also represent attempts to participate in the social, educational, cultural or commercial activities of South Bend without paying the taxes which support them.”– Annexation Report, Page 5

“Since the argument that ‘we are all part of one county’ will never fly, the immediate city problem is survival. This may well involve the recognition that city and suburbs are like separate nations … Since American cities are ‘unwalled’ and no tariffs are in place, foreigners (suburbanites) are free to enter and to exploit city resources. Unlike Jericho – the world’s first city – and the formerly divided Berlin, South Bend and Mishawaka cannot erect physical walls. They could, however, view our jobs and amenities as export items – to be paid for by foreign citizens. Greater user fees for outsiders, an employer surtax for out-of-city residents, higher fares and fees for in-bound commuters, and perhaps even automated toll gates for out-of-city non-tourist entrants are all wonderful things to contemplate.”– Frank X. Steggert. SBT, March 29, 1993. Cites must plan for county war.

“Annexations are one of the few means open to the city to ensure that residents who take advantage of its services and facilities help pay for them. There are a lot of people who want to be a part of South Bend but who don’t want to live here.”– Councilmember Linas “Lee” Slavinskas SBT, March 1, 1994

“The people who live in the unincorporated county areas worry about taxes. The people who live in the city worry about decreasing property values due to ‘white flight.’ There doesn’t seem to be much room to compromise, as one listens to the hatred those who live in the suburban areas when asked about their feelings toward South Bend and Mishawaka. I have entertained the thought of what would happen if the cites in St. Joseph County threw away their incorporation papers and became unincorporated entities. Now that would be worth talking about.”– Joseph T. Zawistowski, April 13,1995

SBT, March 4, 1993

In summary, those who opposed annexation believed South Bend should fix the inner city first before annexing anybody else. County residents opposed the possibility of their taxes increasing while not seeing an adequate enough increase in services to justify the cost. It should be noted that schools – which are often listed as a reason for South Bend’s population decline – are not mentioned by those in opposition to annexation. This is because the areas South Bend pursued to annex were already in the South Bend School District boundaries.

Those who supported annexation claimed county residents in suburbs immediately adjacent to South Bend already received nearly all the benefits of living in South Bend but contributed little to the costs of those benefits. Annexation would provide land for South Bend to grow and rebalance the inequitable situation which developed over time.

The bill passed the Indiana House by a vote of 51-49 and proceeded to the Indiana Senate where Senator Joseph C. Zakas, also of Granger, was the sponsor. This was not Democratic cities versus Republican suburbs. South Bend was led by a Democratic mayor, while Mishawaka had a Republican mayor. Dvorak was a Democrat while Zakas was a Republican. This was city versus hinterlands and city versus suburbs. Even the small towns of St. Joseph County, such as Walkerton and Osceola – who were caught in the crossfire – opposed the bill as it limited their annexation ability as well.

The bill’s history descends into petty politics which doesn’t really affect the subject of this series. In the end, the bill passed and was signed into law. South Bend and Mishawaka sued and, after a number of years, the Indiana State Supreme Court essentially agreed that they were unfairly targeted by the law. In 1999, the state adopted the specific rules established for St. Joseph County to the entire state, essentially ending the matter.

Annexations into South Bend have been rare since the early 1990s, and current analysis would conclude that most of the suburban areas would not generate enough taxes to even pay for the infrastructure needs, especially after state mandated tax-caps have reduced the amount of revenue from residential properties. It’s possible that the entire annexation battles of the second half of the 20th century were a blessing in disguise for South Bend. The city has remained mostly an urban area with limited amounts of suburban sprawl within its borders.

However, “More People” is interested in how South Bend lost 50,000 people in 50 years. One answer to that question is simply that almost all new household growth took place outside the South Bend city limits. When the city attempted to rectify the situation, the suburbs did everything they could – even changing state law – to keep South Bend out.

The imaginary line which separates South Bend on the right and unincorporated residents in Centre Township on the left. Is one really South Bend and the other not?

In the end, annexation is moving imaginary lines on a map. People cross them throughout their days without even noticing. The line matters, but it rarely defines what is the city and what is not. The line matters when we talk of equity. Should one group of people within the borders pay for services that all enjoy? The people within the lines are poorer on average and a far larger share are minorities. As stated above, South Bend provides a large amount of services for all St. Joseph County residents.

However, what services do the suburbs provide for South Bend? I have honestly struggled to come up with any. South Bend – while having the best paying jobs – has the poorest residents. The people who hold South Bend’s jobs live in these very suburbs which fought so hard to keep South Bend out. It matters that this happened.

Despite the common narrative, South Bend continued to grow after the 1960s. The problem is the political imaginary lines which we use to determine what is and is not South Bend failed to keep up with the physical growth on the ground. This failure came from a concerted effort by those who left South Bend for greener pasture just outside the city and who were determined to keep it that way.