Here and There at the 4-H Fair

When we arrived at the County 4-H fair last Friday evening, we parked in the grassy field just west of the entrance.

One of us got out of the car and looked down the rows to the posts with big numbers on them. “What are we?” he said. “Twelve? Okay, twelve. We gotta remember that. One time in LA I lost my car in a parking garage for two and half hours. The security guard had to drive me around in his golf cart to look for it. Ever since then I’ve paid close attention to where I’m parked.”

We laughed and marched on towards the gates, passing every sort of car you can think of, pulling our pockets empty and holding our hands aloft as security made a perfunctory swipe of scanners down our fronts and backs.

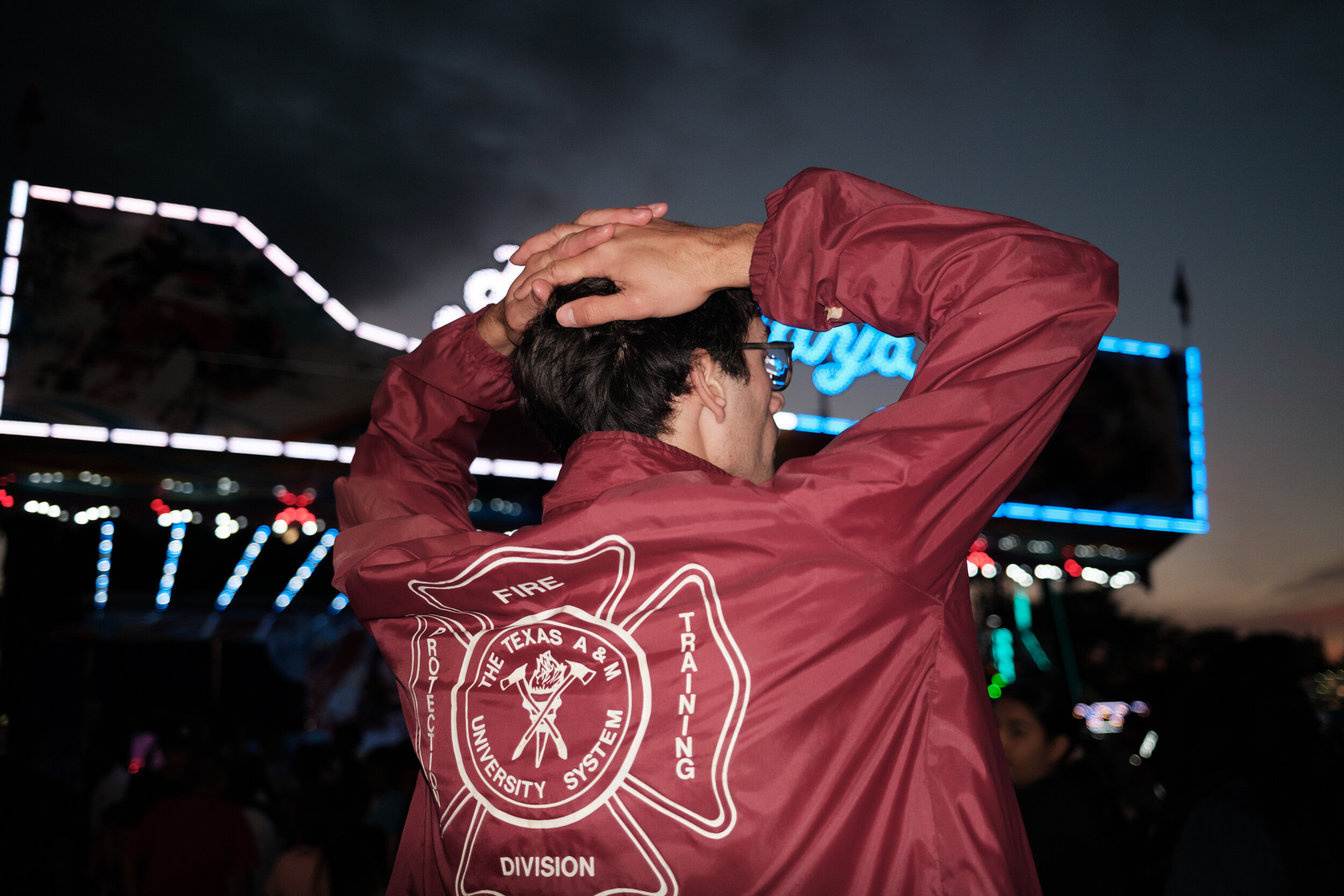

Inside, the air was thick with a mix of oils, from the deep fryers and the rides’ gears. The grounds were packed, shoulder to shoulder in some places where the lines for rides were fifty or sixty deep. Dusk approached, but still the sky was bright blue.

“I’m going to take pictures while it’s still light,” someone said, darting off into the crowd. I tried to follow him with my eyes, but after a moment he was gone, disappeared, to be found only when he wanted to return.

“I’m hungry,” said another. “How about those sirloin tips?” Four of them waited in line. I stood outside the sirloin pavilion, watching the chef pull great hunks of meat from below and slap them around on the grill, tonging them left and right, flipping them over and then tossing them to the side when they were ready to be cut. I looked around at the swarms of people. I saw every sort: big, small, families, loners, people wearing nearly nothing, and three nuns in full habit.

The four emerged, paper boats of beef in hand for three, mashed potato for the vegetarian.

“Why don’t we go look at the cows?” I said. All five of us started towards the cow barn. Two turned back at the door, feeling that it was in poor form to watch the cows while eating their brethren. The cows stood calm at their spots, blinking their great lashes in a slow rhythm.

At the end of the barn was a lone cow, her companions already tucked into trailers awaiting their next destination at the end of the long week. As we got closer, I heard a low crackling noise, as if someone were stepping on trash over and over, and saw that she had an empty water bottle in her mouth. She was chomping up and down, pulling the water bottle further into her mouth and then spitting it out. Surely this wasn’t ideal? we agreed. Surely she was likely to swallow too far and get it caught in her throat?

When she had spat it out halfway again I took the chance, shot my arm out, and made a grab for it. The bottle was covered in saliva and was too slippery to grip. I took a few more passes and finally caught hold of it by the lid. I held it up triumphantly. The cow looked at me, her dark eyes endless, until I broke away and tossed the bottle in the garbage nearby. Then I wiped my hand on the grass.

Our photographer had rejoined the beef-eaters, and we rejoined them once out of the barns. We started off towards the games and rides.

There was shouting from all sides. The first game we saw was Fill-Er-Up, in which players aimed a squirt gun at a bulls-eye, floating a toy of some sort up to the surface of a tube. The woman running the game seemed to be talking without taking breaths in between. “Water, water, water,” she called into her boom microphone. “Who’s in to win? Don’t just stand and stare, hold your five in the air. Five dollars!”

Someone passing by called right back at her to quiet down.

“I will not quiet down!” she snapped. “This is my job right here. I’m going to shout even louder because of you.”

A few blocks down we found the basketball hoops. The man in charge there spoke even faster than the water woman, shouting down at anyone who passed within fifty feet of him.

“All right camera,” he said to our photographer friend. “Taking some pictures, having a night. Why not take some shots?” We walked far enough to be out of range, but close enough to keep watching. A teenager went in the other direction.

“All right, Lil’ Bow Wow,” he said, presumably in reference to the braids, but without realizing that the joke was twenty years late. The teenager didn’t bite. An older man did though, handing over his bills: ten dollars for five shots. The man took the ball from the attendant, bounced it once or twice, twirled it in the air, and then let off a shot with impeccable technique. The ball soared in a perfect rainbow, landed on the inside of the rim and…ricocheted violently away. My eyes fell to the game’s poster. “Rims not regulation,” it said.

Again and again the man shot, and again his balls bounced far away, as did the next shooter, and the next. I didn’t understand why they had made it so difficult to score: the only prizes were oversized stuffed animals, which couldn’t have been more than twenty cents to buy in bulk. They would have even more shooters if there was a chance at winning. But maybe I was missing the appeal, I wondered aloud. Does anyone play those games to win? Does anyone want the stuffed animals? Or do they play them to lose? To lose at the same games and miss out on the same prizes as they did last year, and every year before since their first carnival, to lose at the same games and miss the same prizes as their parents, a ritual unchanged since Eisenhower was in office.

We’d seen enough. Anyway, four of us had re-upped on food, with funnel cakes, elephant ears, and ice cream cones that we wanted some space to enjoy. “Imagine if an elephant came to the carnival,” I said to our ear-eater. “And saw that big sign for ‘elephant ears.’ I’m not sure when he’d be more upset—when he learned his ears are for sale, or when he saw what they were actually selling and thought: ‘Hey, those aren’t elephant ears!’”

As we pushed our way through the crowd, towards the more vacant half of the fairgrounds, we saw a whole cluster of police. Four or five on foot had their heads on a swivel, their walkie-talkies calling a staticky emergency. Two on horseback sat still, looking down from above. Then a crowd of people moved, running towards the gates. The police ran to follow them, and the horses did two, their mounts blowing a piercing cry on their whistles, and speeding up to a trot when onlookers parted for them.

“I wonder what happened,” one of us said.

“Who knows?” I said. “There are so many people around. I can imagine someone making a wrong step and starting something.”

By then we had passed out of the crowds, passed the midway and the fun slide, the shakers, the Himalaya, the bumper cars and the kiddy rides, again passed Fill-Er-Up, where the woman had been replaced by a man who was shouting the same phrases as she had, but while staring at his phone and without any of her enthusiasm, past any more interest in eating.

We were by the stage, watching the Toonas play to a small crowd. They reeled through a series of classic hits as well as any band of high schoolers could be expected to.

During “Summer of 69,” a few of us broke off to look at the lines of tractors parked nearby. “They’re Olivers,” we noticed at once, from the rickety ones restored from the 20s to the gleaming machines that rolled off the line last when it halted forever in 1976. They’ll never make another Oliver tractor, but as long as there is a 4H fair in St. Joseph County, the tractors will be there as sure as the ovular basketball rims and stuffed animals.

“You know how it works,” the singer said to the crowd. “A band starts off playing covers and then writes their own music. This is an original song of ours, and it’s called ‘History Repeats.’” It was by far their best number, beginning with a long guitar intro and a hammering drum line. The keyboardist, who had briefly abandoned her post for a few songs to slap her leg and sing, returned to the keys and tinkled out some melody.

“History repeats,” they sang, and as we cheered their set and headed back towards the crowds, towards the gates and our way home, we didn’t doubt that it was true.