South Bend's Shameful Role in the Desegregation of America's Pastime

On April 15th, 2022, Major League Baseball celebrated Jackie Robinson Day, recognizing 75 years of integrated professional baseball. While every American knows the story of Jackie Robinson, fewer are familiar with the role in that story played by Branch Rickey, president of the Dodgers baseball team. Robinson alone had to face the jeers, threats and hatred on and off the field, but it was Rickey who decided the time was right to sign the MLB’s first black player, despite opposition from coaches, owners and players. His decision forced the issue into the open and required the nation to reckon with this injustice.

Still fewer people are familiar with the shameful yet pivotal moment in this story that played out in our own South Bend, IN - a moment that reverberated throughout Rickey’s life and helped convict him of the need to root out the deeply held prejudice at the heart of America’s Pastime.

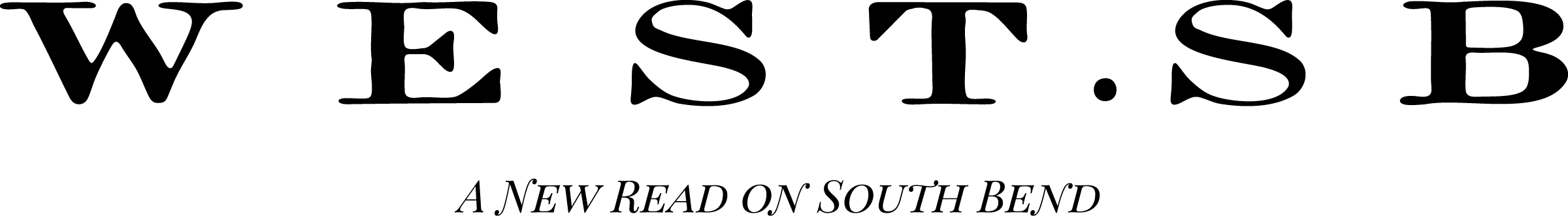

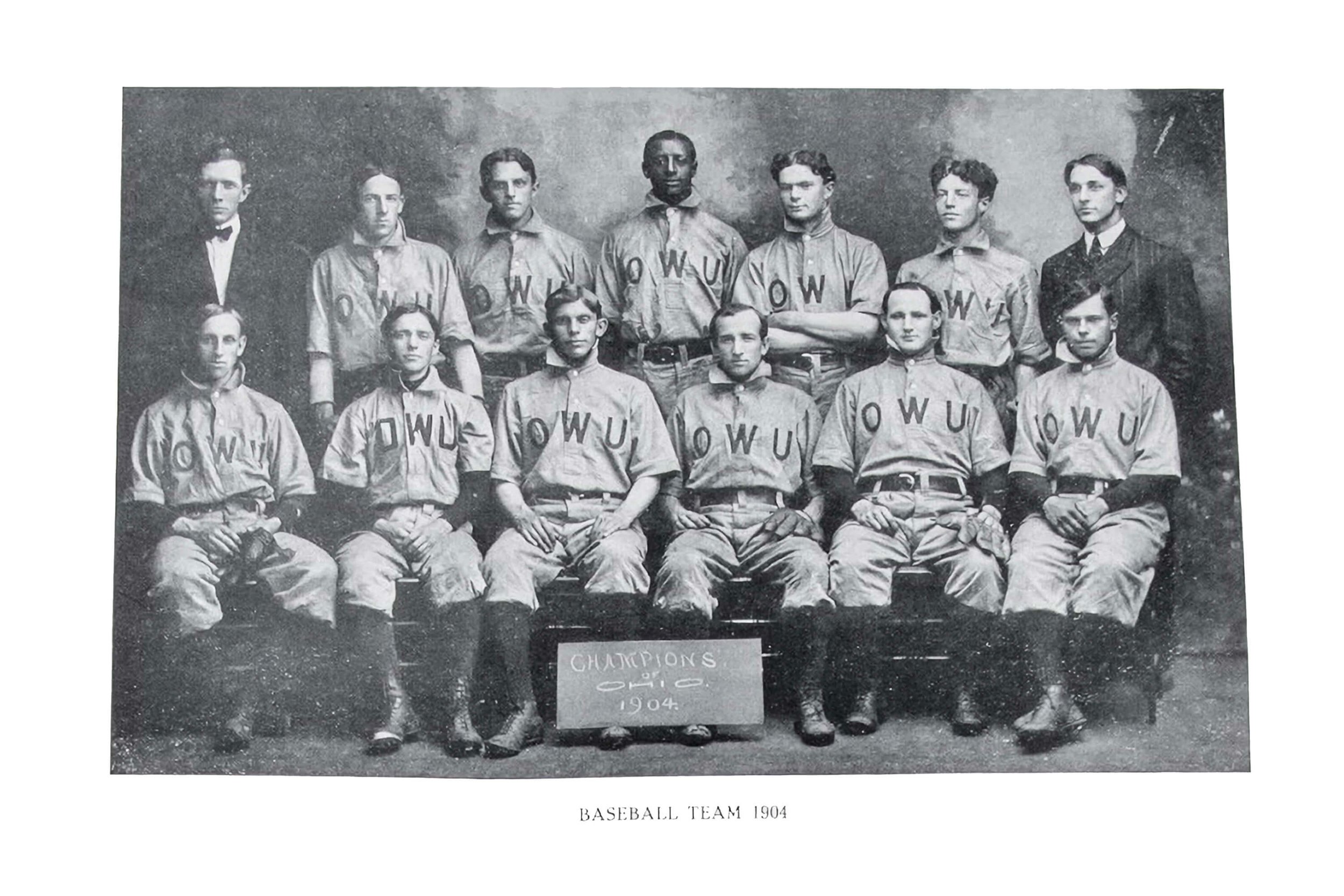

In 1903, a young Branch Rickey was coach of the integrated Ohio Wesleyan University (OWU) baseball team. Their star catcher was black student and Ohio native Charles Thomas. OWU records note multiple occasions where the team was turned away from visiting fields - at times, opponents even forfeited their games rather than play against an integrated team. One OWU alum attended a baseball game against Ohio University which he later recounted in the student newspaper: “The only unpleasant feature of the game was the coarse slurs cast at Mr. Thomas, the catcher.” He continued, “But through it all, he showed himself far more the gentleman than his insolent tormentors, though their skin is white.”

Rickey was always the first to defend Thomas, who later recalled, “From the very first day I entered Ohio Wesleyan University, Branch Rickey took special interest in my welfare. As the first Negro player on any of its teams, some of the fellows didn’t welcome me too kindly…But, I always felt that Mr. Rickey set them straight.”

1905 Ohio Wesleyan Transcript

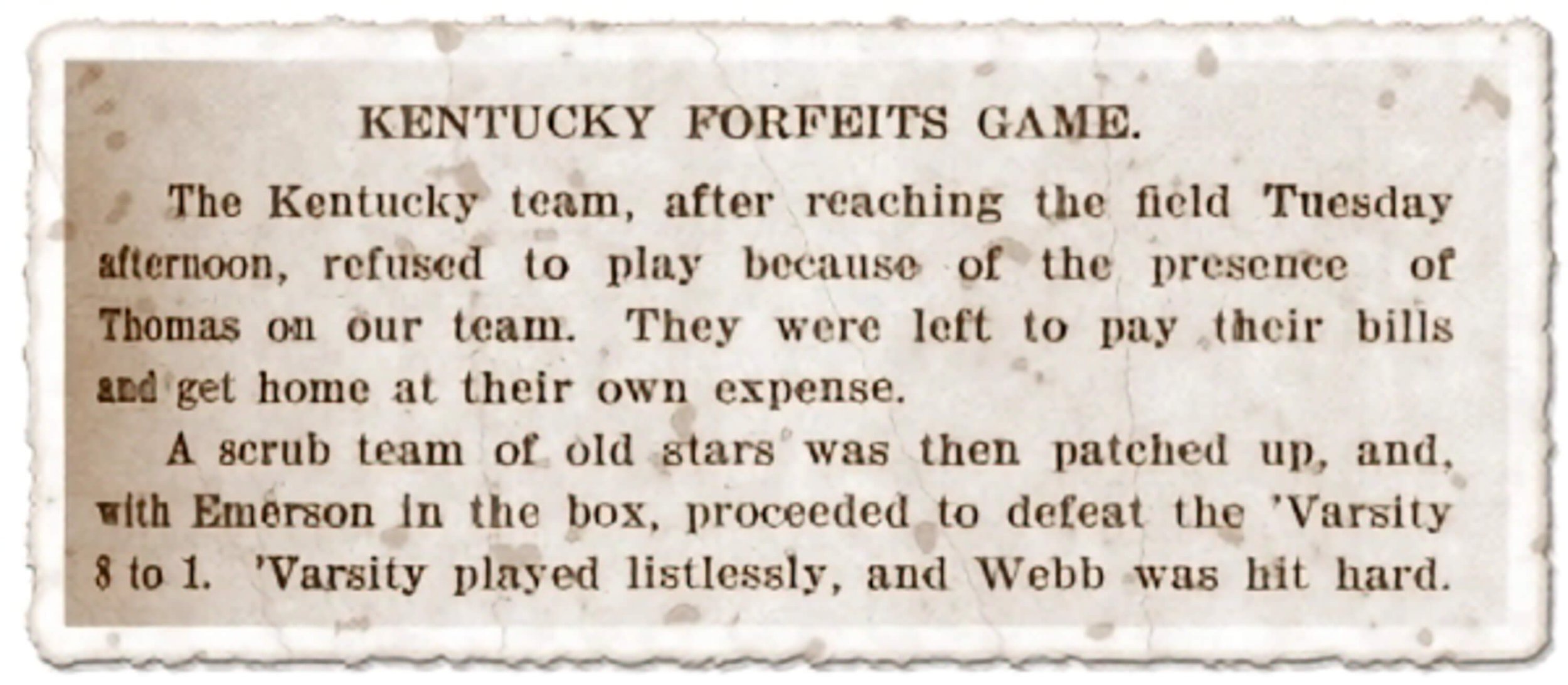

In 1903, the team traveled to South Bend to play a game against Notre Dame. They had arranged to stay at the famous Oliver Hotel, located on Washington Street across from the courthouse, at the site of the current Liberty Tower. As they checked in, the hotel clerk was quoted as saying, “I have rooms for all of you — except for him,” pointing at Charles, “...our policy is whites only.” After some discussion, Rickey convinced the hotel to let Charles stay in his room on a cot, an arrangement he had often been forced to make.

After getting the rest of the team settled, Rickey made his way up to the room. Upon entering, he found Charles Thomas sitting on a chair, sobbing. Rickey would later say that Charles turned to him and cried, “It’s my skin. If I could just tear it off, I’d be like everybody else. It’s my skin, it’s my skin, Mr. Rickey!’” This encounter haunted him. When asked for the motivation behind his decision to sign Jackie Robinson, Rickey described a lifetime of encounters with racial prejudice in baseball but would often quote this specific incident as an essential turning point.

In fact, he recounted this story on the day Jackie Robinson played his first game with the Dodgers on April 15, 1947, 75 years ago. He told the Associated Press, “I vowed that I would always do whatever I could to see that other Americans did not have to face the bitter humiliation that was heaped upon Charles Thomas.”

It took 45 more years after South Bend’s own citizens humiliated Charles Thomas for major league baseball to be integrated. By then, those players who jeered and taunted Thomas were the businessmen, teachers, professionals, and baseball coaches who continued to uphold an unjust system. We now find ourselves 75 years beyond Jackie Robinson’s historic opening day. How many of those who opposed his inclusion have had a hand in shaping the world we inhabit today?

As we celebrate how far we’ve come, let us all remain committed to rooting out the prejudice and racism that still persist in the systems and structure of South Bend and beyond.