One Night at BABY BAR

Before South Bend, I had only ever lived in places that were swelling, at or just beyond critical mass. Cities on either coast where the narrative was always growth, always more, always urgent, with people arriving in droves every day with an idea, a dream, or a promise of knowing the next best thing. Competition first, community second. Before South Bend, I had never lived anywhere where the prevailing movement drifted outward instead of inward.

Most notably, it is the first place where I have felt the presence of absence. Entire blocks feel paused. Storefronts wait and buildings seem like they’re holding their breath. The residue of a larger past is everywhere, along with the quiet weight left after an industry recedes. To the untrained eye, it can read as loss. But if you stay with it – as I only recently learned to – the feeling shifts, and the gaps begin to look like warm invitations.

BABY BAR was our response.

Its chosen location was an old loading garage on Tutt Street, lodged into the far northwest corner of Vested Interest. Like so many places in this area, the building had lived a dozen industrial lives before I ever set foot in it. It began as a turn-of-the-century factory, then later became part of Ziker’s Cleaners, and eventually stood quiet for years before being brought back into use. The garage itself had once been a loading bay, then a stalled storage room crowded with old pianos, broken furniture, and years of dust. It was heavy with history, but it still left enough room to imagine.

In other cities, a space like that would already be resolved, with its use decided before you ever stepped inside. Here, it remained unfinished. The garage on Tutt Street was still open to possibility.

The idea was never to open a business, but to test what it feels like to make a place on purpose. To use a structure that had already held many things and ask it to hold one more, and to see how a small city responds when you invite it to something intimate, simple, and fleeting.

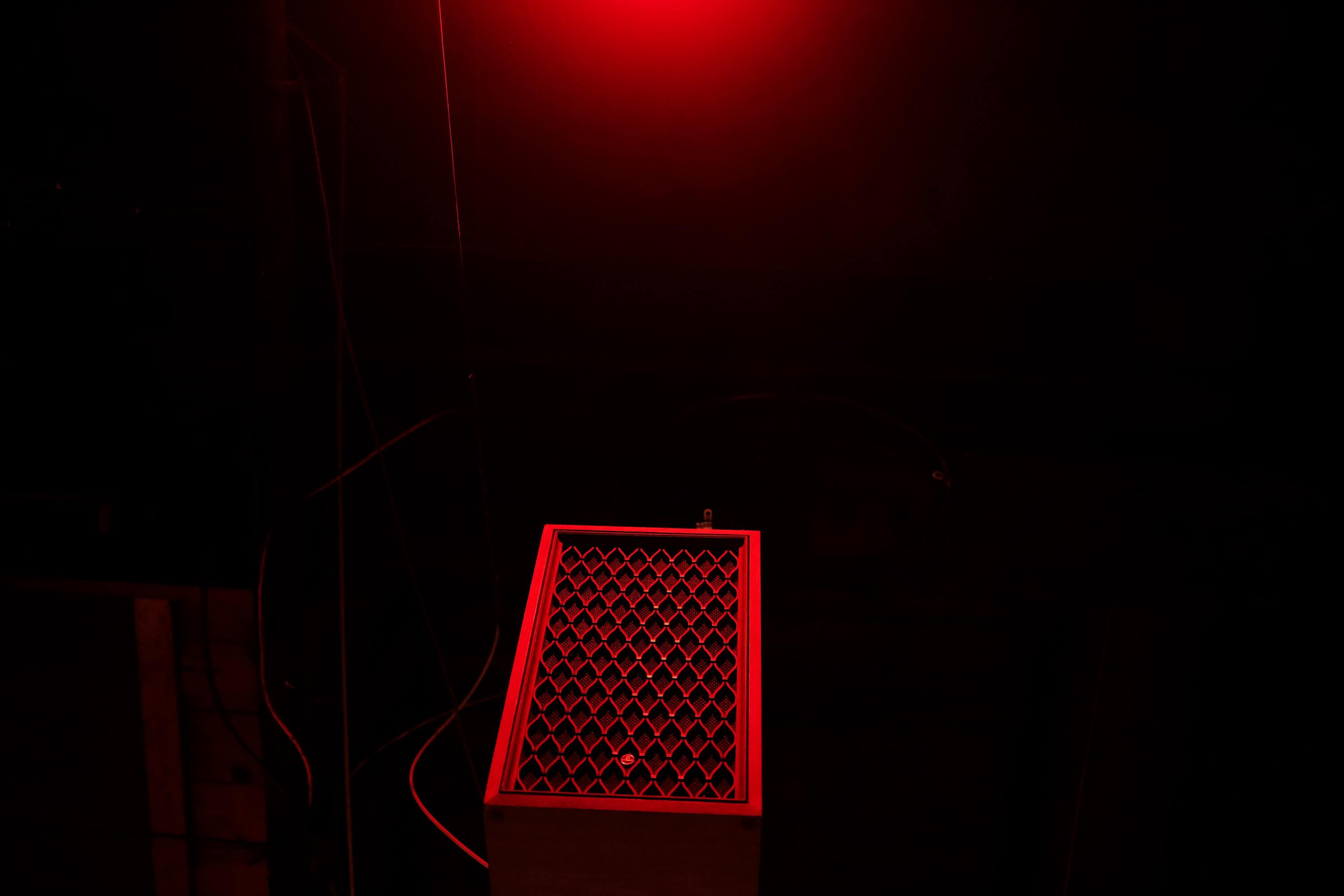

On the night of BABY BAR, people arrived right on time. Some had heard about it online or from friends. Others wandered in because they saw light coming from a space that is usually dark. They entered through a half-open garage door, unassuming enough that you might miss it. The only hints were a set of block letters hanging from a bracket twenty feet in the air, spelling B-A-B-Y, and the flicker of a disco ball slipping out from under the door. Eventually, it was the crowd gathered outside, laughing and smoking, that told you you were in the right place.

Inside, the space had been transformed. We built the bar from scratch with lighting, seating, a bit of signage, and a soundtrack. Together, those elements gave the room a sense of collective discovery. The scale set the mood: small, close, reckless, and romantic. Because of state liquor limitations, we only had beer and wine to work with, so we embraced the constraint. Spritzes, highballs, and simple mixed drinks built from vermouths and amari – evidence that you do not need a full back bar to make a night feel generous.

What I love most about projects like this is watching a room change identity in real time. An old storage garage becomes an empty room, then a bar, and finally an experience once people step inside. The guests complete the place. What surprised me was how quickly it became a small experiment in how South Bend gathers, and a chance to watch people move through a space that did not exist the day before and discover what made them want to stay.

And they did stay. In true Midwestern form, they brushed shoulders, talked to strangers, and lingered longer than they planned. They focused on the people in front of them, on the group they arrived with: were their drinks full, did they have water, were they comfortable. Conversations turned toward what it feels like to be here now, toward corners of the city they love and the ones they wish someone would care for. Inside that garage, the city felt both bigger and cozier, more tightly knit in the best possible way.

That evening, I felt the particular creative energy that lives in a place like South Bend. It is slower and more personal than the pace of other cities, shaped by people who stayed, people who returned, and people who arrived without needing to prove anything. This kind of work is made possible because there is space: physical space, of course – you can still find a waiting garage or storefront or entire building – but also mental and emotional room. The stakes are lower. The pressure to impress is softer, and there’s a belief that what once made South Bend vibrant still exists today, ready for new forms.

With this care also comes a heightened sense of noticing. This city notices small changes. When something appears where there has been nothing for a long time, people pay attention. They ask about it later. They tell their friends. The next time they pass that garage, they see it differently. A place with many memories now holds one more.

BABY BAR showed me that South Bend has the appetite for small experiments and careful hospitality. Our pop-up is just one example – one evening inside one old structure. But it reminds me why I like being here. South Bend gives you room to try things. Room to care about atmosphere and gather people without pretending it needs to become anything larger. Sometimes the most interesting work comes from places that are not bursting at the seams. Sometimes it comes from the quiet city with the open door.

For this transplant, South Bend filled a space in my heart I didn’t know was open. That night, the city became a warm room in early October—a drink in my hand, a neighbor not yet met. I understand now that the blank spaces here are not empty, but waiting.