On finding belonging in empty spaces.

Read MoreThe George Cutter Company of South Bend was once the largest municipal street-light manufacturer in the United States. Their lamps lined cities across the country with warm light and cast ornamental detail. Beauty in the public way.

Read MoreA note on care and neglect.

Read MoreOne man’s field guide.

Read MoreOne man’s weather report.

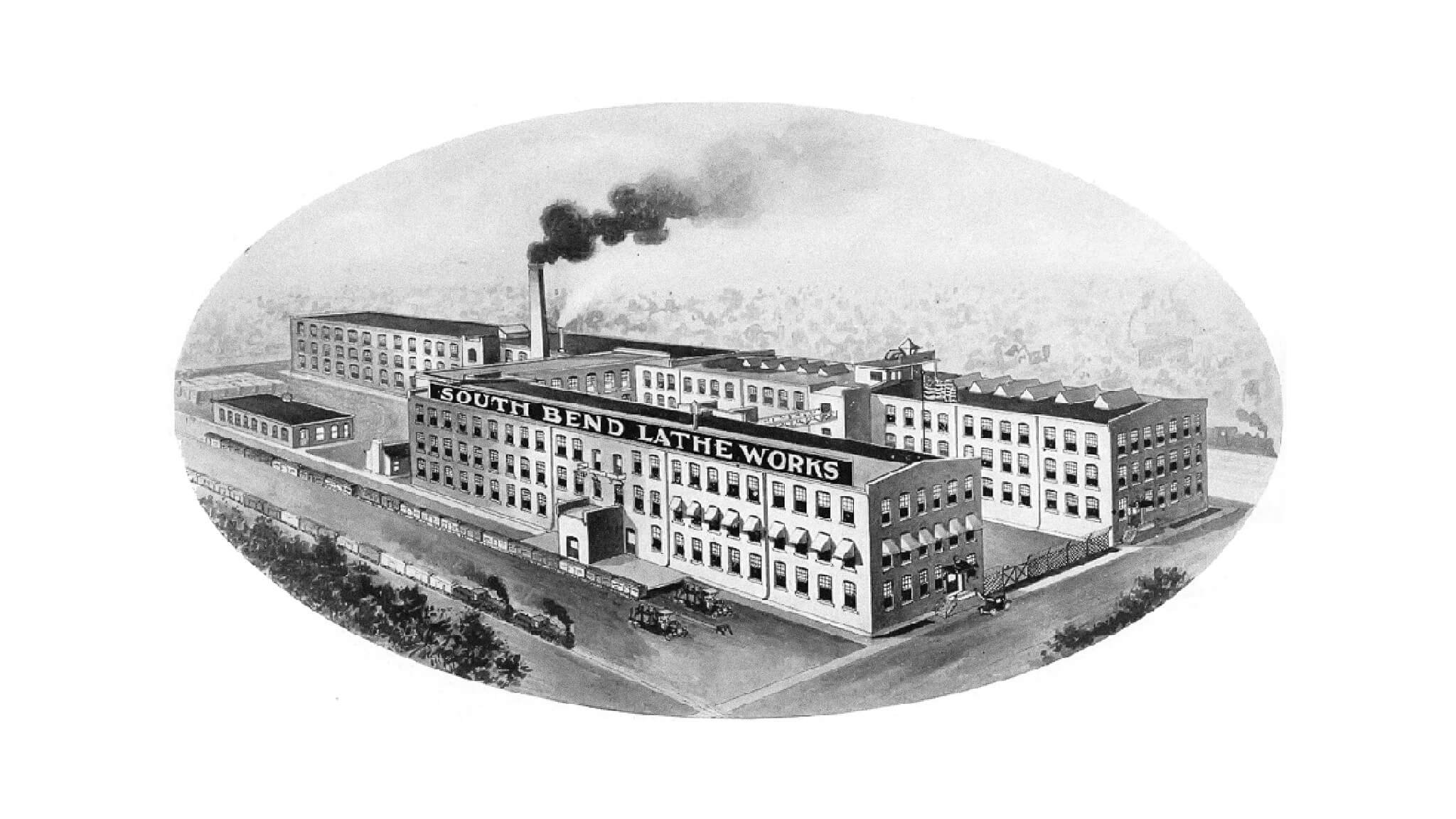

Read MoreOver the last 75 years, South Bend has been at the center of two quintessential stories of change in the industrial Midwest: first, Studebaker in the 1960s, and later, South Bend Lathe in the 1970s.

Read MoreSouth Bend has never became noted as a summer resort, but the possibilities seem to be rather large if the matter should be taken up and pushed. Here are forty photographs from the days I spent in South Bend this summer.

Read MoreI first pulled into Butte, Montana on a Monday in August and took a room at the Finlen Motor Inn. I was in town for a wedding, showing early with my camera and fifteen rolls of 35 mm film. I found it a place fluent in loss and in life, in stories of beauty, bricks, and work. I walked its streets for hours on end, and on the last night, I met a girl.

Read MoreA reflection on a photograph.

Read MoreI’m opening the studio on the evening of Tuesday, June 10 to share a new print project. You are invited.

Read More